By Albert Fuzailof

Star Wars was a game changer for the toy industry comparable to Superman’s first appearance: comic books before Action Comics #1 mostly consisted of reprinted newspaper strips and funny animals. The entire medium changed with the success of Superman. Scores of new superheroes appeared every week, and sales skyrocketed. The industry came alive with new artists and writers competing to create the next sensation, helping to usher in the Golden Age of Comics.

Similarly, there were successful toy lines before Star Wars. Disney merchandising reigned supreme since the 1940’s. Mattel’s Barbie and Hasbro’s G.I. Joe were notable toy lines of their time. But until Star Wars appeared in theaters, there was no single toy line that embodied a universal “I gotta have it” urgency.

Star Wars had a major advantage: it was a 2-hour commercial for Star Wars toys. The space opera gave the Kenner toy line context and purpose, allowing kids (and adults) to relate to a particular figure or vehicle.

Barbie and G.I. Joe were generic, relying on kids’ imagination to give them context and form a bond. But the component of relatability that translates into repeat sales was missing. Toy companies saw Kenner’s success but had no way of replicating it. The challenge now was how to access this untapped market.

Commercial Television was governed by the NAB, FTC and FCC who limited kids’ advertising to appease watch groups that insisted kids can’t tell the difference between content and advertising. As a result, direct advertisements for toys on children’s shows could only include a very limited amount of animation.

In his book, The He-Man Effect, Brian “Box” Brown, describes a chance meeting between Marvel Editor-in-Chief, Jim Shooter, and a Hasbro executive at a party, in 1981. The executive described the problems toy companies faced, being limited in TV advertising or use of animation in advertising aimed at children. He noted that Comic books were not restricted by these regulations.

Shooter proposed to create a comic book series that would provide context and exposure for a toy line, while Hasbro would advertise the comic on TV. Allowing Hasbro to bypass the strict rules. There were no restrictions on advertising a comic book series on TV. The ads for the comic could feature 30-second, action-packed animated sequences with characters and vehicles.

Once details were worked out, Shooter went on to put together a team for the new book.

Larry Hama, who was an editor and writer at Marvel, later described the difficulties in putting a team together. “When the idea was proposed to the staff, it was met with snickering and disinterest. Many of the writers that were approached looked down on the project. No one wanted to be involved with a comic book based on a toy line”.

Another problem was the stigma associated with war toys, particularly on the heels of the Vietnam War. Many refused to work on it on principle.

The final obstacle was financial. Marvel had a set budget for any given series, which included artist/writer fees, printing and distribution, etc. G.I Joe, would entail paying a licensing fee to Hasbro, which would be taken out of the writer/artist end. So, anyone agreeing to work on G.I. Joe would be taking a salary cut.

Larry, a third generation Japanese American and a Vietnam vet, recounted: “My office was the last one, and I was desperate for any work. I had no assignments for a while, nothing in the pipeline either. When everyone else in the offices in front of mine turn down the project, they finally got to me, and I said sure”

The universe that Larry Hama created, with its heroes and villains, went on to great success. Within three years the comic became Marvel’s top-selling subscription title. By 1987, it was receiving around 1,200 fan letters per week.

The success of G.I. Joe prompted Marvel to experiment with its own toy line. Marvel Superheroes Secret Wars” a 12 issue comic series, written by Shooter.

This new method, pioneered by the Hasbro-Marvel model, evolved to include production companies. Now that animated content was a proven concept, toy companies had an interest in creating a rich “universe” for their toys via animated shows.

Mattel’s He-Man and the Masters of the Universe (1983), Hasbro’s Transformers (1984), LJN’s ThunderCats (1985) and a dozen more franchises dominated the TV screens.

The G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero comic has been re-printed and translated multiple times around the world. The animated series and subsequent animated and live action movies were all based on Larry’s work. G.I. Joe also went on to sell quite a few toys.

<img class=”wp-image-550479 alignleft” src=”http://www.comicsbeat.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/a-person-smiling-for-the-camera-ai-generated-cont.jpeg” alt=”A person smiling for the camera

AI-generated content may be incorrect.”>

Albert Fuzailof is the showrunner of Cosmic Con, the premier comic book, sci-fi, and fantasy convention in Queens, New York. In 2025 it expanded and moved to New York City. Follow him on Instagram.

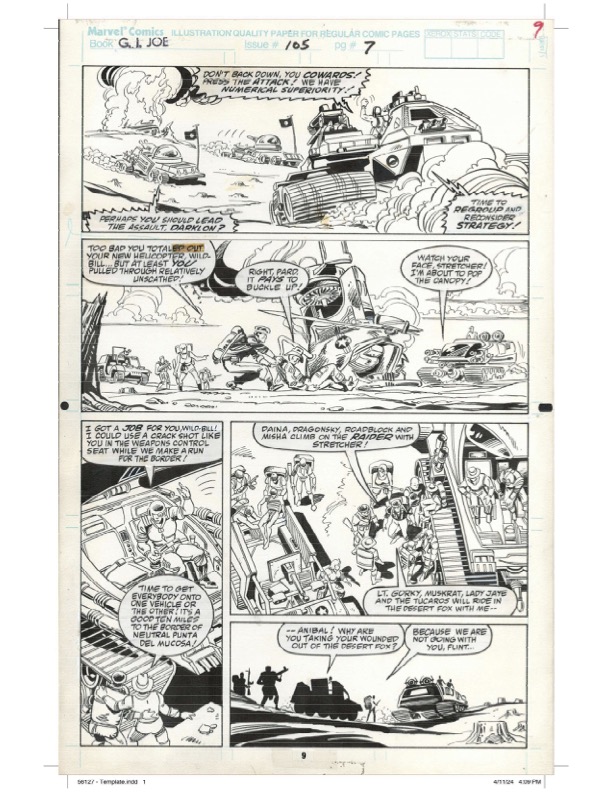

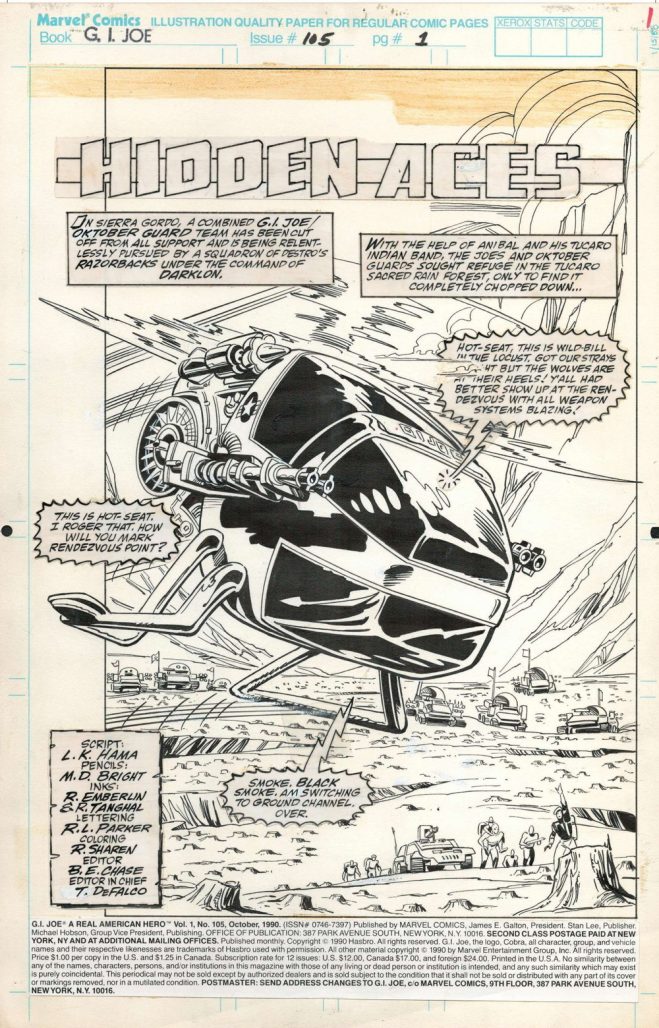

A Brief History of G.I. Joe will be featured in a comic book format of the same name, with several pages of original artwork from issue #105, as well as an article by pop-culture historian Roy Schwartz, originally featured on CNN (2024) and cover art by Joe Rubinstein.

A brief History of G.I. Joe will be available at Mr. Hama’s signing event at Royal Collectibles in Queens, NY on November 13. 2025

17 hours ago

2

17 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)