The effects of depression may infiltrate your very bones – and conversely, your bones may send penetrating messages all the way back to your brain.

This two-way street is a captivating new field of research that could be crucial in improving patient care, especially for older adults, argue three neurologists in China.

In a new review, the authors detail the under-appreciated "bone–brain axis" theory and how this concept can help us better understand and treat a 'silent killer' like osteoporosis and a complex neuropsychiatric disorder like depression.

Their conclusion is that the bone-brain axis, once considered a speculative construct, now "represents a legitimate physiological network."

"The clinical implications are substantial and immediate," argue the authors – Pengpeng Li from Xi'an Aerospace Hospital, Yangyang Gao from Ningxia Medical University, and Xudong Zhao from Jiangnan University.

"Clinicians across relevant specialties should recognize the interconnected pathophysiology of these conditions."

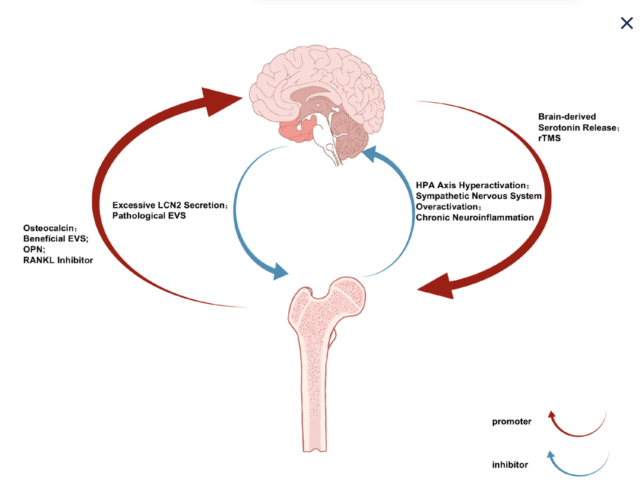

The two-way street of the bone-brain axis. (Li et al., Biomolecules, 2026)

The two-way street of the bone-brain axis. (Li et al., Biomolecules, 2026)Both osteoporosis and depression are common issues among older patients, and often, they go hand in hand. Substantial research has shown that patients with depression frequently face skeletal issues, like reduced bone density.

Conversely, patients who have osteoporosis, which is a disorder characterized by low bone mass, tend to have higher rates of depression.

The two co-existing conditions could have real molecular and cellular connections uniting them, argue the review authors – and the bone-brain axis may be the bridge.

At first, the squishy human brain and our dense, hard bones may not seem to have much in common, but our scientific understanding of both follows a similar historical trajectory.

The human brain was once thought to be 'hardwired', and yet we now know this crucial organ is, in reality, exceptionally malleable, changing with age and experience.

The same can be said of our bones.

The review authors say our traditional view of the mammal skeleton has "fundamentally transformed" in recent years.

Emerging evidence suggests that bones are hormone-producing entities that can profoundly impact distant organs, like the brain.

For instance, a hormone released into the blood by our bones, called osteocalcin, can cross the blood-brain barrier and impact cognitive function.

Acutely depressed patients have shown increased levels of osteocalcin in their blood, which are reduced when depression is treated. This suggests the hormone is somehow tied to mood.

Another bone-derived protein, called osteopontin, shows an anti-inflammatory role in the brain and can actually remodel neurological tissue. Genetic studies suggest that those who have gene variants related to the production of osteopontin are more susceptible to developing depression.

Turning the tables, it is also possible for depression to impact the health of our bones. Chronic hyperactivity of stress pathways is common in those with depression, and it can lead to bone loss through the secretion of brain-derived hormones, like cortisol, and cascading inflammatory responses.

In other words, the severity of depression and osteoporosis may feed into one another via the bone-brain axis.

Exploring this pathway further could help us find a better way to handle these two hard-to-treat conditions. Li, Gao, and Zhao suggest a future for customized exercise programs, neuromodulation, or drugs that focus on bone-derived signals associated with mood and bone health.

Related: New Breakthrough to Strengthen Bones Could Reverse Osteoporosis

A 2025 review, for instance, discusses emerging evidence that exercise can engage the bone-brain axis, triggering effects that may alleviate neurodegenerative diseases, osteoporosis, or mood disorders.

"Future investigations must validate axis-targeted interventions through rigorous clinical trials, but the current knowledge already supports incorporating this conceptual framework into patient management strategies," write Li and colleagues.

"By acknowledging the fundamental connections between mental and skeletal health, we can develop more comprehensive approaches to improve outcomes for vulnerable populations."

The study was published in Biomolecules.

.jpg) 1 hour ago

2

1 hour ago

2

English (US)

English (US)