The islands of Bermuda are a scientific mystery. Not because of the notorious Bermuda Triangle nearby, but because they're perched atop a swollen mass of the Earth's crust that technically shouldn't be there, at least not according to traditional theories.

Now, two seismologists, William Frazer of Carnegie Science and Jeffrey Park from Yale University, have come up with an explanation.

Geologists have long puzzled over Bermuda's existence: The Bermuda archipelago is made up of 181 islands, the outcroppings of a shallow mantle layer formed by a volcano around 33 million years ago.

Usually, volcanic island chains like this (Hawaii, for instance) feature a series of volcanoes of consecutive ages, some current volcanic activity, and a deep-rooted mantle plume.

Related: First Signs of a 'Ghost' Plume Reshaping Earth Detected Beneath Oman

This plume is what typically supports the seafloor's 'swell', which is a geological term for a bulging mound in the seafloor usually created when hot, buoyant material rises from below, like a pimple forming under your skin.

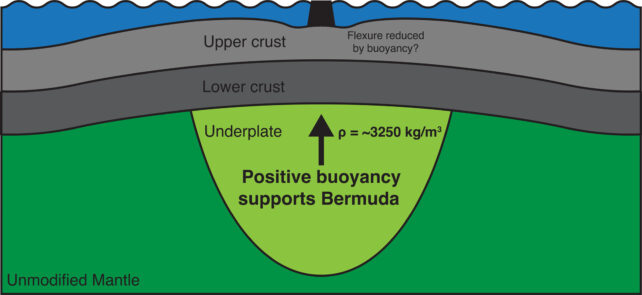

This illustration shows the underplate that could be helping Bermuda 'float' above water. (Frazer & Park, Geophys. Res. Let., 2025)

This illustration shows the underplate that could be helping Bermuda 'float' above water. (Frazer & Park, Geophys. Res. Let., 2025)Bermuda definitely has a swell, but apparently no mantle plume. Given there's no sign that volcanic activity has occurred there for millions of years, the swell (and the islands it's pushing up) should really have receded into the ocean by now. And yet, they have not.

Frazer and Park trawled through records of the rumbles created by earthquakes as they passed through the Earth's mantle below Bermuda. These vibrations can move through dense materials much faster, while less dense matter slows them down, so the waveforms they create can give us a sense of what's going on down there.

In this case, the seismologists found evidence that a layer of relatively low-density rock, about 20 kilometers (12 miles) thick, is doing the job a rising mantle plume usually would: uplifting the crust with its buoyancy to create a swell that holds the archipelago just above its crystalline waters.

"We identify features associated with a ~20-kilometer-thick layer of rock below the oceanic crust that has not yet been reported," the researchers explain in their paper.

"This thick layer beneath the crust likely was emplaced when Bermuda was volcanically active 30–35 million years ago and could support the bathymetric swell."

This 'underplating' is just one possible interpretation of the seismic data. But it could be the one thing stopping Bermuda from disappearing into the Atlantic Ocean, at least until sea levels rise higher.

The research is published in Geophysical Research Letters.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)