The process is very different from rifting as pictured above. (Wildestanimal/Getty Images)

The process is very different from rifting as pictured above. (Wildestanimal/Getty Images)

Strange features of a collision point between pieces of Earth's crust are evidence that the structure may be nearing its end, new analysis suggests.

A careful analysis of the complex boundary where four tectonic plates meet reveals that one of the slabs is tearing itself apart. This process is likely part of the normal life cycle of what's known as a subduction zone, preventing the plates from endlessly pushing into each other and erasing geological history.

"Getting a subduction zone started is like trying to push a train uphill – it takes a huge effort," says geologist Brandon Shuck of Louisiana State University. "But once it's moving, it's like the train is racing downhill, impossible to stop. Ending it requires something dramatic – basically, a train wreck."

Related: Earth's Crust Is 'Dripping' Under The Andes, Scientists Say

Earth's crust isn't one huge piece, but multiple giant slabs of rock floating on a slowly-moving, semi-molten mantle. The only thing preventing these slabs from drifting freely is that they are tightly locked together.

Even so, movement does take place. The plates rub against each other, pull apart, and, in some places, dip an edge beneath an adjacent neighbor in a process called subduction.

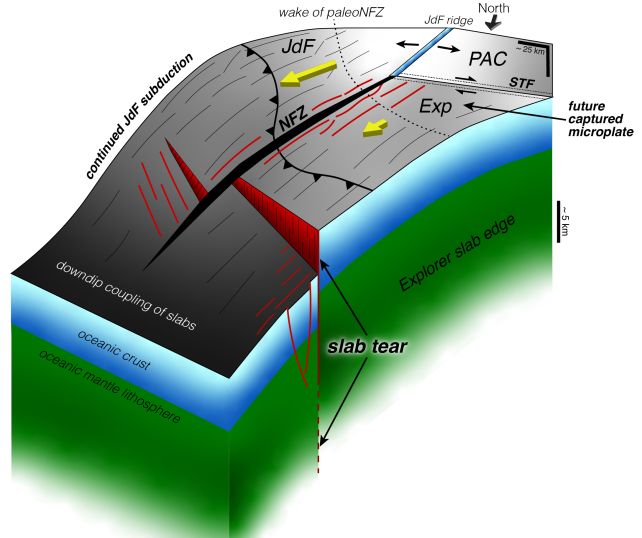

A diagram of the newly discovered processes at play in the Cascadia subduction zone, where the Explorer (Exp), Juan de Fuca (JdF), Pacific (PAC), and North American plates meet. (Louisiana State University)

A diagram of the newly discovered processes at play in the Cascadia subduction zone, where the Explorer (Exp), Juan de Fuca (JdF), Pacific (PAC), and North American plates meet. (Louisiana State University)These overlaps are known as subduction zones, and a particularly gnarly one can be found in the northern Pacific Ocean off the coast of Vancouver Island.

There, in the so-called Cascadia subduction zone, four plates meet: the Explorer, Juan de Fuca, Pacific, and North American plates, with the former two actively sliding beneath the North American plate.

Shuck and his colleagues used seismic imaging from a boat-borne experiment reflecting sound waves off the seafloor and acoustic waves from earthquakes bouncing around inside Earth – like a planet-scale ultrasound – to explore what is going on beneath one particular part of the Cascadia subduction zone, at its northern end.

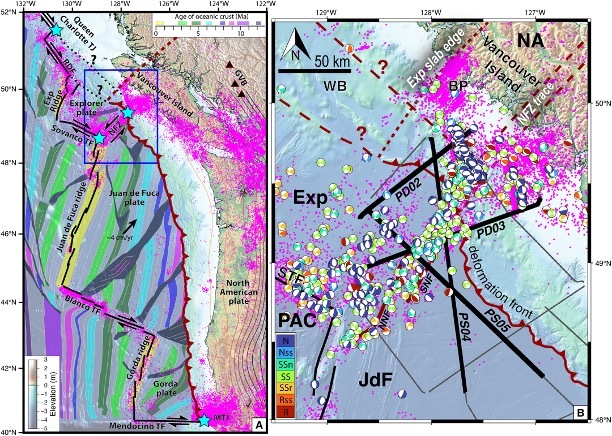

(A) Tectonic structure of the Cascadia margin and subducting oceanic plates. (B) Northern Cascadia study area. (Shuck et al., Sci. Adv., 2025)

(A) Tectonic structure of the Cascadia margin and subducting oceanic plates. (B) Northern Cascadia study area. (Shuck et al., Sci. Adv., 2025)Their analyses revealed multiple large faults and fractures beneath the seafloor where the tectonic plate is snapping under stress – including a very large, 75-kilometer (47-mile) long fault that is actively breaking the Explorer plate. The sections haven't snapped apart yet, but they're not far from it.

"This is the first time we have a clear picture of a subduction zone caught in the act of dying," Shuck explains. "Rather than shutting down all at once, the plate is ripping apart piece by piece, creating smaller microplates and new boundaries. So instead of a big train wreck, it's like watching a train slowly derail, one car at a time."

Evidence for this can be found in the fact that some parts of the plate are no longer seismically active, while others are. This is because the bits that have already broken off are no longer connected to the main subduction system. Eventually, enough material will have broken off that the subducting plate will slowly cease its downward fall because it has less weight pulling it under.

"It's a progressive breakdown, one episode at a time," Shuck says. "And it matches really well with what we see in the geologic record, where volcanic rocks get younger or older in a sequence that reflects this step-by-step tearing."

The research has been published in Science Advances.

.jpg) 10 hours ago

4

10 hours ago

4

English (US)

English (US)