When James Gunn called Superman an “immigrant” in a recent interview with Variety, the media and others freaked out. But no one really denied it. How could they? Krypton, Superman’s place of birth, is very far away. It is also not even real.

And yet.

The reason some people lost their cool is that people tend to fool themselves that Superman is “above” politics. That he is, instead, a “welcome ray of light” or even, “a balm for our souls in these trying times.” All of that is true, of course, but is he still necessarily political? Is he pro-immigrant or antifascist? Or is he just a brawnier version of Mr. Rogers, in the exact same colors? I think he’s all of that, but if you look back at his creation, we can see his true political identity.

As a protest.

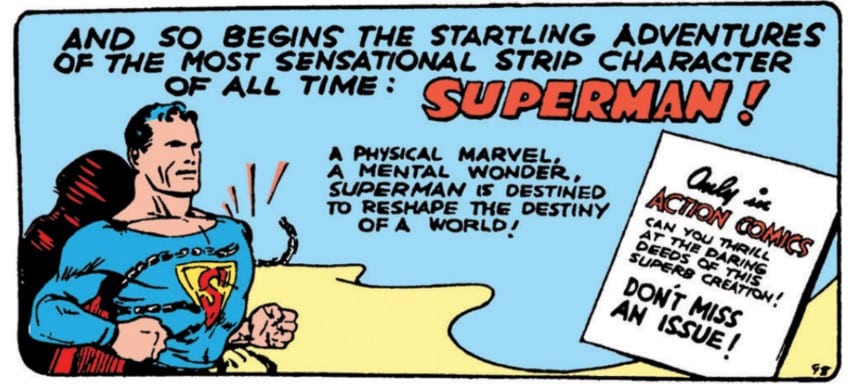

from Action Comics #1 (1938)

from Action Comics #1 (1938)Superman was dreamed up during the early 1930s by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, two friends in Cleveland, Ohio. It is no coincidence that he was also created during the same years that Hitler rose to power in Germany. As the children of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania and Kiev, Siegel and Shuster heard firsthand about anti-Semitic violence and fascist rule. Their parents quite literally ran from it. When they finally arrived in America, they thought Cleveland was far enough away from Europe. It was not.

Like many American cities, Cleveland was home to several German-American organizations that were sympathetic or loyal to the Nazis. They had different names, from the Friends of Germany to the German American Bund to the Silvershirts. The Deutsche Zentrale in nearby, rural Parma was a private farm that boasted summertime amenities such as swimming, a soccer field, and a rifle range. The children ran around and played, their white skin burned red. The bandstand was painted in swastikas.

Summer activities at the Deutsche Zentrale just outside Cleveland, 1937. From Michael Cikraji, The Cleveland Nazis (2014).

Summer activities at the Deutsche Zentrale just outside Cleveland, 1937. From Michael Cikraji, The Cleveland Nazis (2014).There was resistance to these groups. On May 14, 1933, 12,000 people filled Cleveland’s public auditorium to protest Hitler’s immigration policies and his persecution of Jews. They held signs as military veterans including Jews, Catholics, and even Communists booed Hitler (until they were kicked out for doing the same to the national anthem). The result was a Cleveland-led economic boycott of German products, the first in the nation as a means of active protest.

From The Plain Dealer, May 15, 1933.

From The Plain Dealer, May 15, 1933.But the Nazis did not stop. They marched in full uniform in July 4th parades and cheered sympathetic Cleveland mayor Harold Burton with chants of “Heil, Heil, our Mayor!” Leon Wiesenfeld, a veteran Cleveland reporter who wrote for the Jewish World, asked the mayor if he was concerned about the message this might send. Mayor Burton said he would “study it.” Burton would go on to become a U.S. senator before joining the bench of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Cleveland Bund meeting, 1937. From Michael Cikraji, The Cleveland Nazis (2014).

Cleveland Bund meeting, 1937. From Michael Cikraji, The Cleveland Nazis (2014).What did Superman’s co-creator Jerry Siegel think of all this? During this time, he attended high school and worked on the student newspaper, Glenville Torch. On April 21, 1932, Siegel is referenced in a satirical column titled “Impossible to See.” The list includes the impossible image of “Jerry Siegel and Adolf Hitler engaging in a wild game of pinochle.”

In a high school where he was by all accounts a nobody, the only time Jerry is mentioned in the paper (by someone other than himself) is for something the reader is apparently expected to already know in order to get the joke: Jerry hated Hitler.

In 1932. Seven years before the beginning of World War II.

There are other echoes to the Nazi playbook and our own present. Superman’s home planet of Krypton explodes because its ruling council ignores sound scientific data in favor of retaining political power. The young Superman, Kal-el, is saved by his parents and rocketed to Earth in secret. There, he lives on a Kansas farm as an immigrant with a false birth certificate. He becomes a journalist dedicated to the free press, where he frequently writes exposes of the lawless machinations of billionaire tech guru Lex Luthor, who is loudly anti-alien.

When Superman was first published in the new anthology comic book Action Comics #1 in 1938, he appeared along other comics such as “Pep Morgan,” “The Adventures of Marco Polo,” and “Sticky-Mitt Stimson.” Superman stood out immediately, smashing a brand-new sedan on the cover, causing middle-aged men to grab their hats in fear. And why not? The world’s first superhero came out of nowhere and had an agenda. He wasn’t fighting green aliens or giant gorillas. Superman, in his first issue, faces off against domestic abuse, overturns a false death penalty conviction, fights gangsters, and confronts a corrupt lobbyist who is trying to push a senator to get America more “embroiled with Europe.”

Superman began as a response to real current events. Pep Morgan boxed a guy named Sailor Sorenson for the lightweight crown and Sticky-Mitt Stimson stole some produce. They don’t have movies this summer. There is a reason Superman still speaks to us, and it’s not necessarily because he’s so good. It might be because he stands up for us.

In his alter ego, Superman flies around helping people. The “S” on his chest doesn’t stand for hope; it is a placard that rises in the air for his own resistance movement that is antifa and pro-kindness. And because his is a comic book world, when he is attacked by intergalactic fascists such as Darkseid or Mongul, Superman must fight back, with often spectacular collateral damage. But no one really gets hurt. Superman is a protest after all, not a conqueror. He always pulls his punches.

From Action Comics #1 (1938).

From Action Comics #1 (1938).As the world’s first superhero, Superman was a revolution by the time the first brushstrokes by Shuster were still drying in Cleveland. The character strained against all the norms of what children’s literature – and its young creators – should be allowed to do, not only as artists, but as people with political opinions. No one would hear them, so they drew attention to their views with a cape and feats of strength.

The problem is that none of it is real.

Though Superman played a role as propaganda during WWII, he stayed out of the fighting for the most part because his presence would destroy the believability of the story. Think about that for a minute. Hitler didn’t need the Spear of Destiny to keep superheroes away. The truth did just as well. In this 1941 letter to the editor in the Washington Post, 14-year-old Earl Blondheim explains why.

from the Washington Post, Dec. 20, 1941.

from the Washington Post, Dec. 20, 1941.Superman can only be a protest – and not the fight itself – because he is fictional. But a protest can be just as powerful, sometimes even more so. In those raw early comics, Superman is a riot in red and blue. He moves as a force against the fascism that was brewing in Europe, which he fought in places with made-up names like San Monte, Barovia, and Warworld. He still fights this battle nearly ninety years later. The action is fictional, but it remains so astounding, so over the top, so super, that it becomes its own kind of movement, calling us to almost impossibly good work, limited only by the ceiling of our own imagination.

Brad Ricca is the award-winning author of seven books, including Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster—The Creators of Superman. More at brad-ricca.com.

22 hours ago

1

22 hours ago

1

English (US)

English (US)