Exotic states of matter known as time crystals are largely considered a quantum phenomenon. Now, a team from New York University (NYU) has shown that a classical time crystal can emerge in a far simpler way – using nothing but speakers and styrofoam.

This system might not just be an extraordinarily clean example of a classical time crystal, but a really neat laboratory for studying non-reciprocal interactions on a macroscopic scale, where particles interact through scattered sound waves rather than direct, balanced forces.

"Time crystals are fascinating not only because of the possibilities, but also because they seem so exotic and complicated," says NYU physicist David Grier.

"Our system is remarkable because it's incredibly simple."

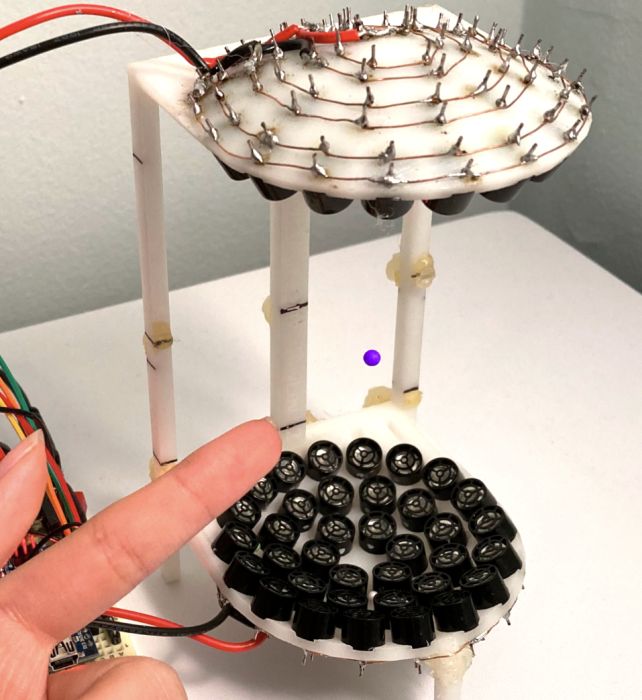

The acoustic levitation system used by the researchers. (NYU's Center for Soft Matter Research)

The acoustic levitation system used by the researchers. (NYU's Center for Soft Matter Research)Time crystals, first predicted in 2012, are even stranger than their name suggests. The term does not describe an object, but a type of behavior, and it all has to do with how patterns repeat.

In crystalline objects, such as quartz, diamond, salt, and a whole range of metals, the atoms are arranged in a tidy lattice structure that repeats in three-dimensional space, like the joints between bars of a jungle gym. Any part of the pattern can perfectly superimpose over any other part of the pattern.

A time crystal is an arrangement of particles that repeats in time, oscillating with a temporal pattern that repeats in such a way that it can also be superimposed, just like a spatial crystal. Critically, this continuous oscillation breaks time symmetry, operating without being set by an external ticking clock or periodic drive, and at a frequency that emerges from the interaction itself.

Many experimental time crystals are quantum systems based on their entangled states. Grier and his colleagues, NYU physicists Mia Morrell and Leela Elliott, discovered their classical system almost by accident while investigating a different class of physical interactions.

Tiny polystyrene beads, just a millimeter or two across, are excellent tools for studying the way objects interact indirectly via sound waves. They're very light, which means they can be levitated using sound waves, but have enough structural integrity to remain rigid under acoustic forces. They also have slight variations in size and shape, which is crucial for studying non-reciprocal interactions.

The scientists conducted their experiments as part of their ongoing research into these interactions. First, a small speaker array was adjusted to produce a standing sound wave – one that is perfectly balanced in structure, with no imposed rhythm. Then, the beads were introduced, creating a tiny disturbance that sound waves bounced off.

"Sound waves exert forces on particles – just like waves on the surface of a pond can exert forces on a floating leaf," Morrell says.

"We can levitate objects against gravity by immersing them in a sound field called a standing wave."

The two beads then interact via the waves each scatters. A slightly larger bead will create a larger disturbance than a smaller one; the force it exerts on the smaller bead will therefore be larger than the force the smaller bead exerts on the larger.

This is what is meant by a non-reciprocal interaction – common in acoustics and optics, but usually small and difficult to experimentally isolate.

Using their apparatus to investigate this phenomenon, the researchers found that when conditions were just right, the interaction between the two beads caused them to oscillate in a temporal pattern, without anyone shaking, nudging, or otherwise introducing a beat.

Related: World First: Physicists Created a Quantum Time Crystal That We Can Actually See

The beads can maintain a stable repeating pattern for hours, settling into a robust steady state rather than a fleeting fluctuation. And just two beads? That's the smallest possible system potentially behaving as a time crystal.

There might not be any practical applications yet, but the findings may entice some other experimental pursuits. For example, some biochemical systems in our bodies interact non-reciprocally. That doesn't mean our circadian rhythms are time crystals, but it raises fun questions about whether similar principles could show up in biology.

It also shows that we don't necessarily need expensive, high-tech equipment to investigate some of the physical world's more exotic behaviors. Sometimes, it seems, you can make do with styrofoam and perhaps a subwoofer.

The findings have been published in Physical Review Letters.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3

English (US)

English (US)