One of the best visualizations ever produced of the spectrum of light from our glorious Sun reveals some mysterious holes in its array of colors.

Most of the thousands of dark Fraunhofer lines in the solar rainbow have been traced to different elements in the Sun's atmosphere absorbing the light at that particular wavelength.

But even with decades of high-resolution solar spectroscopy, there are some spectral lines whose origins have never been clearly identified. That's not for lack of trying – but our Sun is a wilful and tricksome beast whose secrets are surprisingly difficult to uncover.

Related: The Sun Is Being Weird. It Could Be Because We're Looking at It All Wrong

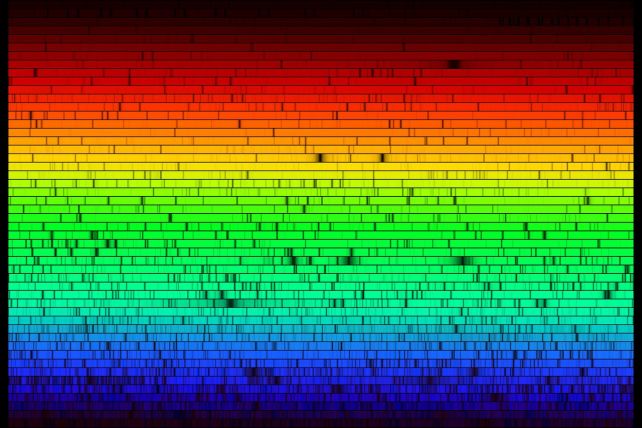

Although our Sun appears to blaze in white light, the particulars of its full spectrum are a lot more complex. The below image shows the full solar spectrum, compiled from observations obtained at the US National Solar Observatory on Kitt Peak in the 1980s.

The high-resolution spectrum of the Sun recorded in 1984. (N.A. Sharp/KPNO/NOIRLab/NSO/NSF/AURA)

The high-resolution spectrum of the Sun recorded in 1984. (N.A. Sharp/KPNO/NOIRLab/NSO/NSF/AURA)There are several remarkable things about the spectrum. One you may notice immediately is that the light is brightest at yellow-green wavelengths, even though the Sun's rays appear completely colorless in the sky (please don't go out and look at it without eye protection, though).

Another obvious feature is the presence of dark patches. These are the Fraunhofer lines, named after German physicist Josef von Fraunhofer, who documented them in 1814. We've known about them for over 200 years, and their mechanism is pretty well understood.

They're absorption lines, and similar features can be seen on every star and galaxy for which spectra can be obtained. They are caused by the absorption of photons at that wavelength by atoms and molecules in the solar atmosphere. Different elements absorb different wavelengths of light; a specific pattern of absorption lines can serve as the fingerprint of that element.

It's a very clever way of finding out what elements are present in a star or galaxy or even planetary atmosphere, but it's rather more difficult than it sounds, especially if multiple fingerprints are visible and overlap.

Even so, most of the Fraunhofer lines have been identified, and that's how we know the Sun – predominantly hydrogen and helium, like all stars – also has a bunch of stuff like oxygen, sodium, calcium, and even trace amounts of mercury.

This is no idle curiosity, either. When the Universe was born, it consisted almost entirely of hydrogen and a bit of helium.

That's actually still the case, but to a slightly lesser extent, because once the stars were born, they started smashing together atoms in their cores to make heavier elements. Then, when those stars died, they not only scattered those heavier elements out into space, but their violent explosions created heavier elements still.

Subsequent generations of stars incorporated those materials into their own formation. The number and array of elements heavier than helium in a star are tools by which scientists can calculate that star's age. Nifty stuff.

Because the Sun is the closest star we have access to, it's the star for which we have the most detailed spectral data.

Despite this wealth of data, hundreds of observed absorption features remain unmatched to the chemistry that created them, or inconsistent with synthetic spectra – a set of absorption features generated by modeling a synthetic Sun based on its temperature, gravity, atmospheric structure, and other characteristics.

There are several reasons for this, neatly documented in a 2017 paper investigating a specific set of missing lines.

Possibly the biggest contributor to the puzzle is that the current databases of atomic and molecular lines, although large, are far from complete. Determining the spectral fingerprint of a specific atom or molecule often requires testing and verification, and some groups, such as the iron group, are particularly complex.

But the Sun itself is also a large part of the problem, with a dynamic and variable atmosphere dominated by convection and wildly changing magnetic fields that can interfere with the appearance of absorption features.

The result is a set of mystery lines in the solar spectrum at wavelengths that don't match the synthetic spectra, and can't be attributed to any known atomic or molecular absorption.

And, honestly, it is pretty cool that, even after centuries of study, the closest star to Earth has some knotty mysteries we have yet to untangle – mysteries that, on a superficial level at least, look more solvable than they are.

The good news is that we're getting closer to finding answers every day. Better instruments, growing databases of spectral lines, and improved atmospheric models of the Sun all contribute to this progress. And every mismatch between the real and synthetic spectra is a clue that tells us how we might improve our models.

At the same time, we'll probably never finish studying our Sun. That's a marvelous thing too.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1

English (US)

English (US)