Just over half a billion years ago, Earth was rocked by a global mass extinction event, a dramatic interruption of the Cambrian explosion of life on Earth.

What happened next, in the direct aftermath of this event, has mostly been a mystery – until now.

A newly discovered fossil site in Hunan, South China, has captured an entire ecosystem in recovery, in extraordinary detail, including soft tissues and internal structures. Nearly 60 percent of the species found within are previously unknown to science.

Named the Huayuan biota, the collection boasts 153 animal species spanning 16 major groups, for a grand total of 8,681 fossil specimens recovered from a single site – and it was all recorded around 512 million years ago, hot on the heels of the Sinsk extinction around 513.5 million years ago.

The richness of species and level of preservation rivals Canada's famous Burgess Shale.

Related: Mind-Blowing New Fossil Site Found in The 'Dead' Heart of Australia

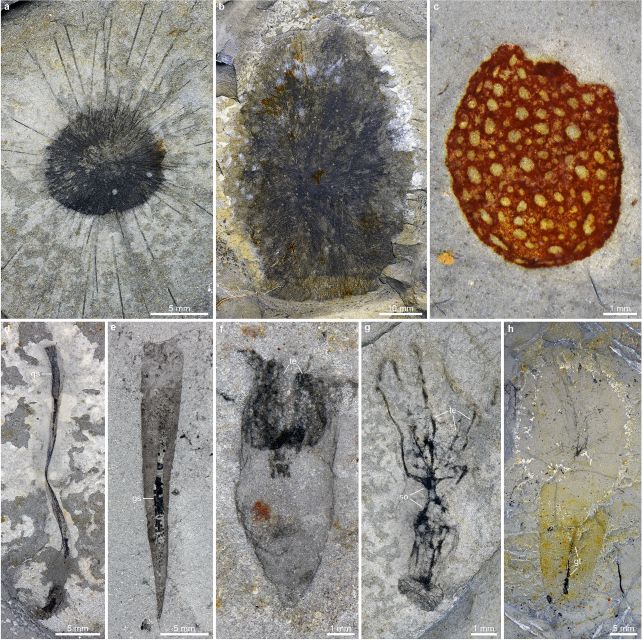

Some of the strange new fossils of the Huayuan biota, including Cnidarians and one spectacular sponge in the top right. (Zeng et al., Nature 2026)

Some of the strange new fossils of the Huayuan biota, including Cnidarians and one spectacular sponge in the top right. (Zeng et al., Nature 2026)Earth has quite a few tricks up its sleeve for fossilization, but the Huayuan biota is truly a shining rarity. It belongs to an elite class of fossil deposits known as Lagerstätten – fossil beds that have both exceptional richness and exceptional preservation.

But it's not just any Lagerstätte; a team led by paleontologist Maoyan Zhu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has classified the Huayuan biota as a Burgess Shale-type (BST) Lagerstätte – the very rarest and finest type of fossil bed, where soft-bodied animals and delicate internal tissues are preserved as a rule, not an exception.

Earth's Cambrian Period, which lasted from around 540 to 485 million years ago, was a time of great change for our planet. It was during this time that the first major diversification of animal life took place – the Cambrian explosion. But the tree of life was trimmed shortly after with the Sinsk extinction event, which may have been triggered by tectonic activity.

Thanks to a handful of BST Lagerstätten from around the Sinsk event, paleontologists have managed to reconstruct some of the effects it had on life on Earth. The Burgess Shale in the Canadian rockies is about 508 million years old; the Qingjiang biota and the Chengjiang biota, both in China, are about 518 million years old.

A new arthropod species, complete with its digestive tract. (Han Zeng)

A new arthropod species, complete with its digestive tract. (Han Zeng)These sites helped scientists discover that, while many shallow-water species were killed off in the Sinsk event, life managed to rebound within a few million years.

Dated to around 513 million years old, the Huayuan biota is a direct window into the immediate aftermath of the extinction event. It shows that at least some ecosystems – namely, deeper waters – served as safe refuges.

The fossils themselves reveal a rich and diverse ecosystem, filled with predators and prey alike. Their preservation includes far more than just their external shapes and textures – in many cases, internal organs and soft tissues were captured in exquisite detail, including nervous systems and even cellular structures.

Other structures preserved include gut diverticula and optic neuropils, offering rare glimpses into ancient digestive systems and nervous tissue. The site will keep scientists busy for many years to come.

A selection of some of the trilobites of the Huayuan biota. (Zeng et al., Nature 2026)

A selection of some of the trilobites of the Huayuan biota. (Zeng et al., Nature 2026)The biota contains arthropods such as trilobites and apex-predator radiodonts, and invertebrates like sponges, comb jellies, and sea anemones. What makes this special is that many of these animals appear to have been preserved where they lived, rather than being swept in from elsewhere.

This means that researchers can make inferences about their behavior; for example, a number of vetulicolians were preserved in groups, suggesting that they shoaled together in life.

Perhaps the most surprising discovery is that of the world's oldest known pelagic tunicate, a group of filter feeders that today play a major role in the ocean's carbon cycle.

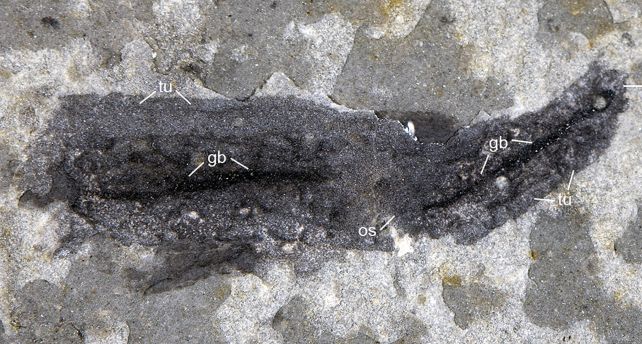

Believe it or not, this black smear is the world's oldest pelagic tunicate. (Zeng et al., Nature 2026)

Believe it or not, this black smear is the world's oldest pelagic tunicate. (Zeng et al., Nature 2026)The presence of free-swimming tunicates in the biota suggests that surprisingly modern-style ocean ecosystems were already taking shape soon after the Sinsk extinction.

The other really exciting part is that the researchers compared their biota with other Cambrian Lagerstätten. They found that the Huayuan biota bears some striking similarities to the Burgess Shale fossil site.

Several iconic animals once thought to be unique to the Burgess Shale, such as Helmetia and Surusicaris, appear in the Huayuan assemblage as well, even though the two sites are separated by thousands of kilometers and millions of years.

It's an absolutely magnificent find, and one that's likely going to become crucial for understanding the Cambrian Earth.

"The extraordinary biodiversity of the Huayuan biota provides a unique window into the Sinsk event by revealing the post-extinction recovery or radiation in the outer shelf environment," the researchers write.

"It indicates that the deep-water environment might have played a crucial role for structuring the global marine animal diversification and distribution since the early Cambrian."

The research has been published in Nature.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3

English (US)

English (US)