Ilustration of a neuron. (koto_feja/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

Ilustration of a neuron. (koto_feja/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

Parkinson's disease is characterized by the death of dopamine-producing neurons in a part of the brain responsible for motor movement. Now there's fresh evidence for how these crucial brain cells are being killed off.

Building on previous studies in animal models showing that as these neurons die, the remaining ones work harder, researchers from the Gladstone Institute for Neurological Disease in the US used genetically modified mice to test the theory that intense bursts of overactivity could be causing the initial damage.

Their experiments showed that when drugs were used to artificially stimulate dopamine neurons in the brains of the test animals for several days, the cells gradually degenerated and then died – specifically in the region for motor control known as the substantia nigra.

Related: Parkinson's Link to Gut Bacteria Hints at an Unexpected, Simple Treatment

"An overarching question in the Parkinson's research field has been why the cells that are most vulnerable to the disease die," says neuroscientist Ken Nakamura.

"Answering that question could help us understand why the disease occurs and point toward new ways to treat it."

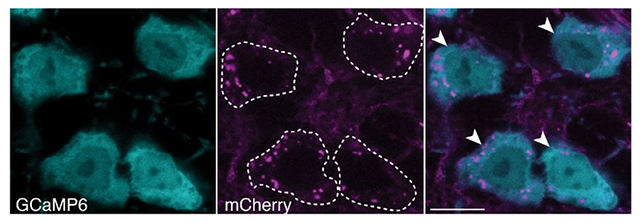

The researchers studied overactive dopamine neurons in mouse brains, finding changes in calcium production. (Rademacher et al., eLife, 2025)

The researchers studied overactive dopamine neurons in mouse brains, finding changes in calcium production. (Rademacher et al., eLife, 2025)As with neuron death in general, it's not clear if the loss of overworked cells could be triggering Parkinson's disease, or if the neurons' exhaustion is more of a consequence of the disease. It may be a bit of both.

It's also undetermined why these cells go into overdrive in the first place. Different environmental and genetic factors could be involved, the researchers suggest, raising questions for further study.

Through a close analysis of the mice brains, the team found that the neurons that were running hot showed changes in calcium levels, and in the expression of genes related to dopamine metabolism and calcium regulation.

A further examination of brain cells from people with early-stage Parkinson's disease showed similar patterns related to calcium regulation and dopamine production. It's as if some of the cells' healthy stress responses had been dialed down.

"In response to chronic activation, we think the neurons may try to avoid excessive dopamine – which can be toxic – by decreasing the amount of dopamine they produce," says neuroscientist Katerina Rademacher, from the Gladstone Institute for Neurological Disease.

"Over time, the neurons die, eventually leading to insufficient dopamine levels in the brain areas that support movement."

The researchers suggest there might be a vicious cycle at work, where overactive neurons die off and then the remaining neurons become more active to compensate. It's a little like lightbulbs becoming too bright and blowing out.

A wide variety of reasons have been put forward to explain why dopamine-producing neurons die off in Parkinson's, from malfunctioning mitochondria (the energy sources inside cells) to harmful protein clumps.

Now there's a new option to consider, which the researchers want to test further: and if this does indeed help explain why the disease gets started in the first place or continues to accelerate, the next step is finding ways to block it.

"It raises the exciting possibility that adjusting the activity patterns of vulnerable neurons with drugs or deep brain stimulation could help protect them and slow disease progression," says Nakamura.

The research has been published in eLife.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3

English (US)

English (US)