Spaceflight may make certain types of human stem cells age faster, a study suggests — but at least some of the damage may be reversible.

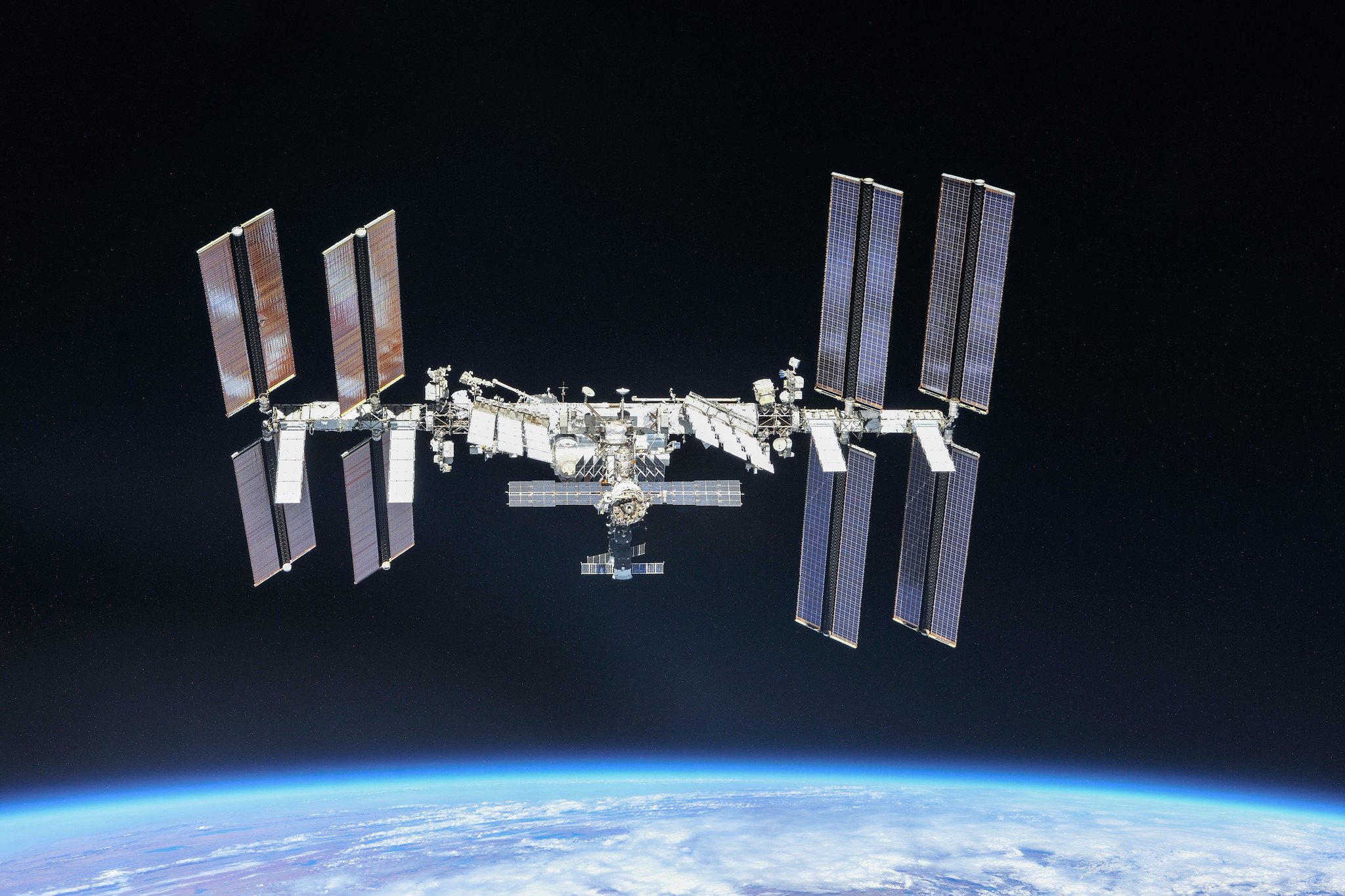

Spending time aboard the International Space Station (ISS) induced aging-like changes in a group of cells key for the health of blood and the immune system, known as hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), a new study in the peer-reviewed Cell Stem Cell journal reports.

"The findings show that the cells lost some of their ability to make healthy new cells, became more prone to DNA damage and showed signs of faster aging at the ends of their chromosomes after spaceflight — all signs of accelerated aging," representatives of the University of California San Diego said in a statement about the study. (The paper's first author is UC San Diego's Jessica Pham.)

According to the statement, radiation and microgravity were likely the chief stressors on the HSPCs, which were made up of four sets sent on SpaceX commercial resupply missions to the orbiting complex aboard the company's Dragon spacecraft.

"Understanding these changes not only informs how we protect astronauts during long-duration missions but also helps us model human aging and diseases like cancer here on Earth," study co-author Catriona Jamieson, director of the Sanford Stem Cell Institute and a professor of medicine at UC San Diego, added in the same statement.

The research is one of many follow-ons to a study on now-retired NASA astronauts Scott Kelly and Mark Kelly, who are identical twins. Scott spent nearly a year in space on the ISS from 2015 to 2016, while Mark remained on the ground during the same period. The Twins Study, as NASA termed the collection of research, "helped scientists better understand the impacts of spaceflight on a human body through the study of identical twins," according to an agency description of the research.

NASA's Twins Study site emphasizes that the human body shows "resilience and robustness" to spaceflight conditions. For example, 91.3% of Scott's gene expression levels returned to normal in the first half-year after his mission concluded.

Some novel findings were observed, however, such as what happened to Scott's telomeres. NASA has said that telomeres, or the ends of DNA strands, protect chromosomes the way that plastic handles protect jump ropes.

"Without telomeres, DNA becomes 'frayed' and damaged, and cells don't work properly," NASA officials wrote. "One of the most striking discoveries from the NASA Twins Study was that Scott experienced a change in telomere length dynamics during his flight. These changes may help evaluate general health and potential long-term risks."

Of the telomeres that lengthened during Scott's flight, NASA stated, most of them returned to normal in just 48 hours after returning to Earth. The new UC San Diego statement stresses, however, that studying telomeres and gene expression changes "could be relevant for longer space missions."

For the new study, which was published on Sept. 4, the researchers created an ISS platform that allowed the human stem cells to be "cultured in space, and monitored with AI-powered imaging tools," according to UC San Diego. The study included HSPCs that were in space for between 32 days and 45 days. (For comparison, a typical ISS mission is six months, or roughly 180 days.)

The research team observed some changes, as well as signs that at least some of the damage could be reversed. Some cells, after weeks in space, began to recover when put in a "young, healthy environment" here on Earth, UC San Diego representatives wrote.

While the statement did not specify what that environment was, the study notes that the cells were placed either into bone marrow layers from the same individual from which they were cultured, or a connective-tissue-promoting cell line from a 30-year-old male donor.

As for the observed HSPC changes, the researchers saw more activity, less ability for cells to recover and regenerate and (inside the cells' mitochondria, the heart of energy production) more stress and inflammation that led to normally inactive genome sections being activated.

The exposed spaceflight cells also had decreased ability to manufacture new and healthy cells. Simultaneously, "signs of molecular wear and tear, like DNA damage and shorter chromosome ends … became more pronounced," the new statement noted.

The university has now concluded 17 missions overall to the ISS, and more launches focused on HSPCs may be coming. UC San Diego plans ISS missions and astronaut studies, including "real-time monitoring of molecular changes" as well as countermeasures.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)