In 1979, NASA's first space station, Skylab, fell to Earth. The intention was for it to crash into the Indian Ocean, but it survived deeper into the atmosphere than anyone expected. Once it finally broke apart, pieces of the lab reached as far as western Australia. The largest pieces of debris landed near the town of Esperance. Pieces of metal were falling from the sky, so town leaders had to do something about it.

They issued NASA a $400 citation for littering. The debt went unpaid.

It was technically a humorous jab, and in 2009, a California radio host raised the funds to pay off the debt. But it highlights how Skylab's fate became something of a joke in the 1970s and how we let a space station fall to Earth without having a replacement waiting in the wings.

And here we are again, nearly half a century later, facing the potential demise of another space station, without having a replacement ready.

At least this time around, however, NASA has something approaching a plan: get someone else to build it.

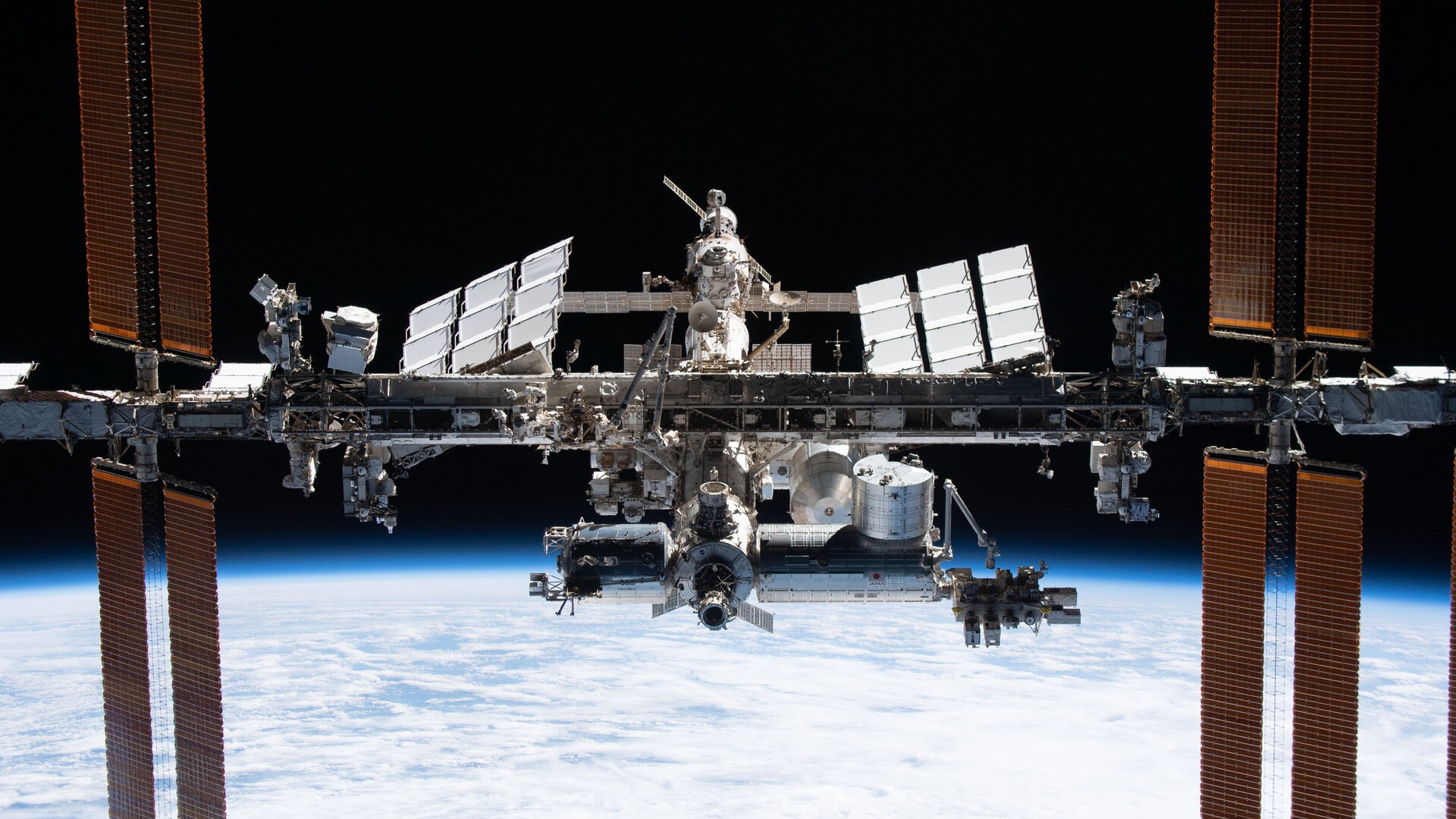

Since the first modules of the International Space Station (ISS) went up in 1998, over 4,000 scientific experiments have been conducted there. They have investigated everything from the effects of long-term spaceflight on the human body to the development of novel materials that can only be designed in microgravity.

Most importantly, we've learned how to operate in space for extended missions — what protocols and procedures we need in place, what kinds of systems tend to go wrong and when, and all the other institutional know-how that it will take to make us a true spacefaring species.

NASA plans to send the ISS into Earth's atmosphere in 2030, and it has no plans for a replacement — at least, not directly.

Currently filling NASA's time and budget is the design of the Lunar Gateway, a smaller version of the ISS designed to orbit the moon and serve as a waystation for extended surface missions. While the Lunar Gateway continues to receive congressional backing, its political future remains uncertain because it's a part of the overall Artemis program, which may not make all of its intended goals.

Either way, NASA is largely leaving behind operations in low Earth orbit. Instead, the space agency has developed a competitive system, called the Commercial LEO Destinations program, to help spur private investment in a space station. The idea is that NASA will fund private companies to create their own stations and then become one of many customers that will rent out time and space on those stations. That way, NASA will not have to do the heavy lifting of creating another iteration of the ISS.

There are several competitors in this area, including Orbital Reef, a joint venture led by Blue Origin and Sierra Space; and Starlab, a joint venture between Voyager Technologies and Airbus. But the clear front-runner is Axiom Space, which is nearly finished with the first module of its Axiom Station.

Axiom plans to launch that module on board a Falcon Heavy rocket and attach it to the ISS in 2027, when the company will begin getting accustomed to the world of space station care and maintenance. Then, presumably before 2030, Axiom will detach that module from the ISS and continue building it out, with a goal of reaching twice the usable volume of the current station.

Axiom already flew private astronauts to the ISS in June, for a practice run of handling ground-crew communication and the operation of scientific experiments.

If Axiom Space or any of its competitors succeed, then we will indeed have another torchbearer for our continuous presence in low Earth orbit, although this time, it will involve many more partners than the venerable ISS. And hopefully, this early public investment will pay off big time as private companies find many commercial uses for low Earth orbit, such as zero-gravity hotels for space tourism or mini-factories for producing specialty materials.

NASA has already seen success with a similar program, the Commercial Crew Program, which spurred and financed the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon spacecraft, both of which now serve both private and government projects. With a little luck, they will avoid the fate of Skylab and the decades-long gap between that station's ignominious end and the launch of the ISS.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3

English (US)

English (US)