Research conducted by two physicists from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the US reveals that clocks on Mars tick 477-millionths of a second (or 477 microseconds) faster per day, on average, compared to Earth clocks.

Though small, that difference could be critical in situations where time on Earth, the Moon, and Mars needs to be coordinated with split-second precision.

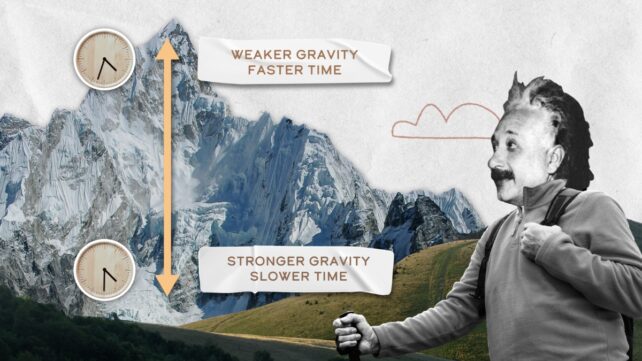

Einstein's theory of general relativity shows time is affected by mass, resulting in what's known as gravitational time dilation. To an outside observer, clocks affected by a relatively strong gravitational field will tick more slowly than the watch on their own wrist.

Likewise, the length of each second within a weaker gravitational field is shorter than the seconds being counted by observers experiencing more gravity.

Related: Scientists Found an Entirely New Way to Measure Time

As an example, atomic clocks on GPS satellites run faster compared to clocks on Earth's surface, as the ever-so-slight change in gravity in medium-Earth orbit, combined with their acceleration's impact on time dilation, creates a net difference of 38 microseconds per day.

Now, NIST scientists Neil Ashby and Bijunath Patla have devised a precise timekeeping system for Mars.

Time is affected by gravity, and gravity is affected by mass. ( J. Wang/NIST)

Time is affected by gravity, and gravity is affected by mass. ( J. Wang/NIST)The physicists had previously devised a timekeeping standard for the Moon, analogous to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) on Earth, which is the global timekeeping standard. Utilized by astronomers and the Deep Space Network (DSN), UTC is accurate within approximately 100 picoseconds a day, with a picosecond being one trillionth of a second.

On the lunar surface, time runs 56 microseconds faster than on Earth, based on major factors like its own mass, as well as the gravitational interplay between the Sun, Earth, and Moon.

But measuring time for Mars is trickier than it is for the Moon, explains Patla: "A three-body problem is extremely complicated. Now we're dealing with four: the Sun, Earth, the Moon, and Mars."

Mars's surface gravity is much weaker than terrestrial surface gravity due to Mars having about one-tenth the mass of Earth. Using data collected by Mars missions, Ashby and Patla estimate that Mars' surface gravity is five times weaker than Earth's.

In addition, Mars sits about 1.5 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, compared to 1 AU for the Earth-Sun distance. Since the tug of gravity decreases with distance via the inverse-square law, Mars is subject to a weaker gravitational potential from the Sun.

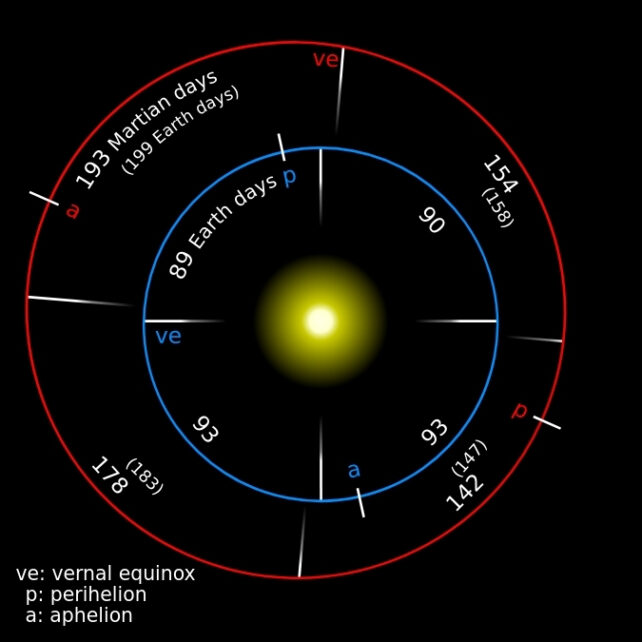

This is further complicated by the fact that Mars has a much more eccentric orbit than Earth's, forcing it to experience greater fluctuations in gravitational potential.

So while Martian clocks run 477 microseconds faster than Earth's on average, this difference decreases or increases by 266 microseconds a day throughout a Martian year.

That Martian year is also much longer than a terrestrial year, as Mars takes 687 days to orbit the Sun. Its day is longer as well, as the red planet requires an extra 40 minutes to complete a full rotation on its axis, compared to Earth.

The orbits of Mars and Earth, with the seasons in red and blue, respectively. (Areong/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0)

The orbits of Mars and Earth, with the seasons in red and blue, respectively. (Areong/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0)Achieving these precise, scalable temporal frameworks is imperative for future operations on Mars, including a fateful and historic human touchdown.

"It may be decades before the surface of Mars is covered by the tracks of wandering rovers, but it is useful now to study the issues involved in establishing navigation systems on other planets and moons," says Ashby.

In the intervening period, off-Earth timekeeping will be crucial to support communications, positioning, and navigation for the lunar missions planned by both commercial entities and national space programs.

Building scalable timekeeping infrastructure beyond the Earth-Moon environment and creating a framework for "autonomous interplanetary time synchronization" is therefore an essential goal, so this research realizes a vital step for space exploration.

Patla highlights the importance of these findings: "The time is just right for the Moon and Mars. This is the closest we have been to realizing the science fiction vision of expanding across the Solar System."

This research is published in The Astronomical Journal.

.jpg) 4 hours ago

2

4 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)