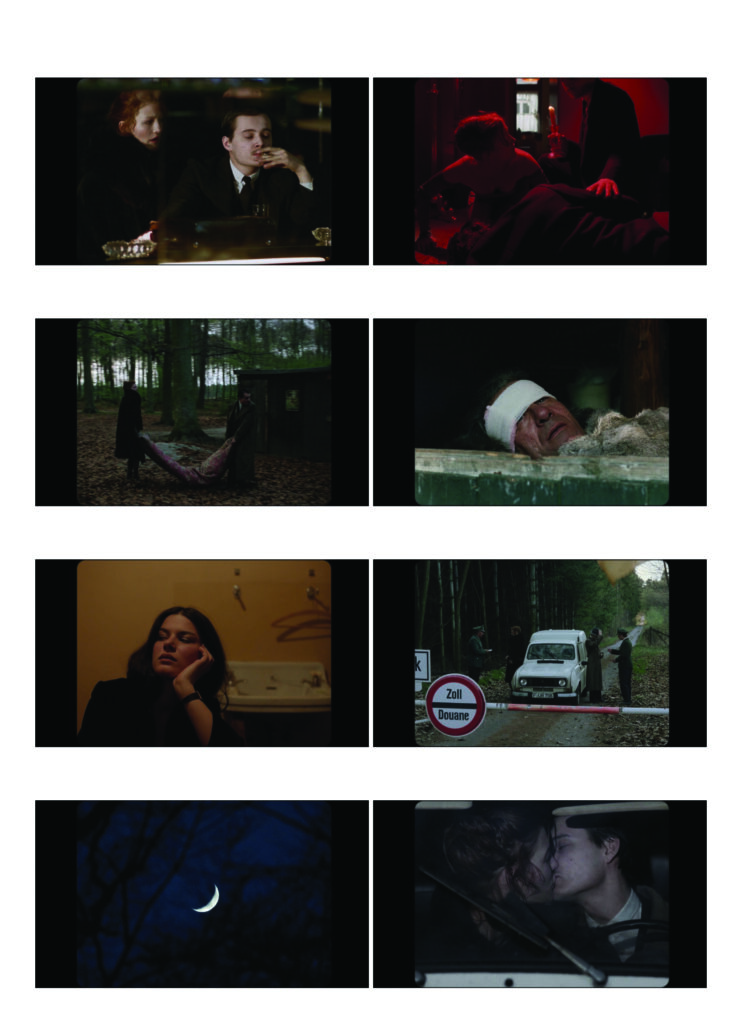

Film stills from Die Macht der Gefühle (The power of emotion), final sequence: “Undoing of a crime by means of cooperation,” 1983. All images courtesy of Alexander Kluge.

ARRIVAL OF SUNDAY’S CHILD

Things went on until three in the morning. The child, arriving in the world at 11:55 P.M., bathed, photographed, placed in the young mother’s arms, still counts as a Sunday child.

At this point the servant girls are in their rooms, too. All the drunk well-wishers have sunk down onto the sofas and across the floor of the salons and are fast asleep. The day following the excitement is a Monday. The girls clean up the remains of the feast. The head doctor is already in his office. Patients are coming up the stairs to the waiting room. The female doctor is asleep.

The child in the room next to the female doctor has been “forgotten” for a few hours. Although all carry the “news of the happy event” in their excited hearts, the basket with the child itself has been put away and it will be noon before anyone thinks to ask about the new arrival’s regularities.

First, the flowers in the winter garden need to be stowed away. Stocks from the pantry brought to the cleaning woman’s family. They are considered to have been “used yesterday.”

The young doctor can hardly believe that, at all of twenty-four years of age, she managed a birth. She’s got earplugs in, is fast asleep. Were visitors not expected to come to congratulate the “Sunday child” during the afternoon, you could easily forget that piece of meat in the basket, even if it screamed.

Next to my mother. Around ninety-five minutes after my birth. The clock on the nightstand shows a little after 1:30 A.M. Wrapped up nice and warm. Friendly eyes all around. Presumably, I have not yet begun to perceive them. Everything up close. Presumably, I am not “thinking” about anything. My bowels are painstakingly learning to “work.” My entire system is undergoing conversion. The beginning of my long march.

THE LONG MARCH OF BASIC TRUST

There is a fundamental mistake to which all living creatures that have found their way to us through evolution—in other words, that have survived—cling: basic trust. For evolution this mistake seems to be an advantage. After birth, people immediately believe—and we assume that animals do, too—that the world means well. A complete mistake. Marx would say: “A necessary false consciousness.” The world does not mean well.

And yet we live from this trust. This is a treasure, which, until the end of our lives, none of us give up too easily. Our ability to envision horizons is based on this. It is what Nietzsche means when he is doubtful about our being truth-seeking creatures and says that we are “immersed in illusions” instead. And without any doubt we spin cocoons about ourselves which warm us on the inside.

Thomas Combrink

THE EXPRESSION “BASIC TRUST”

The expression “basic trust” goes back to the German American psychoanalyst Erik H. Erikson, born 1902, died 1994; his book Childhood and Society deals with the concept. It has to do with the first months of a person’s life, when practiced habits together with a caregiver’s affection create lasting confidence. For Erikson, the earliest evidence of trust in reality is the smooth sequence of bodily processes; that the feeding, digestion and sleep of the newly born human being run smoothly. The child’s first feat of abstraction concerns its ability to allow its mother out of its field of vision. The child carries its closest caregiver in its heart because it can rely on ingrained habits, on the spontaneous elimination of unwillingness. Regarding trust, Niklas Luhmann speaks of “overdrawn information.” This is the opposite of control. “Trust is based on illusion. In reality, there is not as much information as you need to be able to act with confidence. The person acting deliberately ignores the lack of information,” Luhmann writes.

COOPERATIVE BEHAVIOR

Following the air raid of February 11, 1943, the charred remains of a human being were found in a building in Blaubach. One of the occupants maintained that it was her husband. Another woman from the same building came forward to say that her husband had been in that bombed-out cellar, too; in fact, the two had probably been sitting next to each other. Which meant that they were the bodily remains of her husband then as well. She, too, would like to be able to visit a grave. The occupant who had returned to the rubble first suggested that they share the charred man’s odds and ends.

BACK TO BASIC TRUST

If I desire to be a good parent, I don’t really want my child to fly down the stairs. But how else will it learn?

In Halberstadt I learnt to the meter how to do harm to one’s bones. In Halberstadt, where I was born, as each one of us is born somewhere. But from my first days and experiences I am now going to make a jump. I am a gauge, like all human beings, an echo chamber, making its way through the world and trying to write down and measure everything. A bat, in other words.

BASIC TRUST AND BASIC FEAR

I do not trust basic fear, as it is, so to speak, a kind of inverted form of basic trust, a basic trust that has been disappointed. And as far as emancipation is concerned, fear is a very poor counsellor of self-consciousness. There is a certain politics of balance to self-consciousness. For example: Siegfried destroys everything due to excessive self-consciousness, he has no equanimity, he doesn’t listen to anyone or anything beyond the birds in the forest, he upsets the whole court of Burgundy and works for its downfall; a solo effort on the part of self-confidence. I would place much more trust in quieter forms in which self-consciousness can unite with another self-consciousness in a quasmusical way, in which the two halves of our brain can correspond with each other as well. There is something paralyzing about fear. Incidentally, I do not believe that there is such thing as a basic, primal fear, it is not primal, it is always a matter of experience.

If I know that I sprained my arm when I flew down the stairs as a child, I can metaphorically fly down the stairs more often in my future life. Fear is translatable. There is a hysterical fear that is necessary in any nervousness, for example. We are simply not alert without a certain amount of hysteria. There is certainly a fear of depth, something that the Romans call numen which can also contribute the fear of god. People need a quantity of it like a vaccination. It’s like a garment, like a tank. Under certain circumstances it may protect, but doesn’t motivate, it isn’t productive. To live we need a more powerful motive than fear.

Here we come into a rather complex form of alchemy because we human beings require everything. An order in Napoleon’s army was

“Jaccia feroce,” ferocious face, his soldiers were to adopt faces absent of fear. No superior or partisan leader can control their soldiers if they forbid fear. It must be allowed to live. Put another way: All of the sensations we have are to be designated as the ability to discriminate. The Enlightenment philosophers in France were known as amis d’analyse, friends of analysis, friends of the ability to discriminate. This is an original position of the Enlightenment. A mass production of this ability to discriminate is that which connects us as human beings, and this includes the entire sphere of fear, too. Hearing stories is a great source of satisfaction, as is talking confidentially and sharing our fears. Fears diminish, shared fear is less dangerous, and a relationship of trust develops. Being able to admit what you are afraid of is proof of trust. Being able to tell someone about your weakness—fear is often weakness in this sense—and not being penalized for it creates trust. The motive is trust, not fear. What sets things in motion is the motive, the supply, so to speak, the fuel.

A SATURDAY IN OCTOBER 1929

The BASIC IDEA was not what Dr med. Erwin Zacke would later claim to his wife: that they should enjoy a comfortable life for a few more years before having children, but SUSPICION, CAUTION. The way they were sitting together no basic idea could arise. After morning drinks, they just sat around until midday (it was a Saturday), then continued to sit together until evening drinks, waiting for a snack that the maids were preparing in the kitchen.

– It would be a sin not to do it. In a quarter of an hour, we’re done (Zacke said). Everything’s here. Karl (Erwin’s friend, surgical colleague) does it the short way.

– Is it painful?

The young woman would actually have liked to keep her child but didn’t want things to be cumbersome. It was a matter of illusion. She could imagine being a young mother and she could imagine being “free of parental duties,” “we can go traveling.” And though they were still sitting around the table, dressed, she was uneasy about being touched in an intimate place by the guest who, as the more experienced doctor, was to perform the operation. She was undecided.

– Not everyone can have something like this done on the weekend and in their own house to boot. This is luxury (the husband said).

He was overdoing it, for seizing the opportunity was not his motive. He had married the young woman just about two months previously within one week of having met. But he was unsure whether she was “untouched,” hadn’t checked at the right time. He didn’t want to appear “medical” at that moment either. So it now seemed more “prudent” for him to get rid of the child, if with regret in the case it had indeed been conceived by him.

– Let us sit here in peace for a while (the young woman said).

– Karl can do everything in a quarter of an hour (Erwin answered).

– Not against her will (a guest opined).

– I’ve got to think (said she).

She wanted to win some time.

Those at table together were fairly drunk. This condition benefited the defense of the womb because it made those involved sluggish.

– It is now 5:45 P.M. (the zealous one warned). If we want to be finished by 6:30, we’ve got to get going.

– Don’t be pushy.

– If we’re done by 7 P.M., we can slice the ham and set out a cold duck. The Liesenbergs are coming at 9, and at 11 there will be hot sausages.

– Now that’s what I call a program (Karl, the head surgeon, said).

– Let me think about it (the young woman resisted).

If she’s this interested in the child, Erwin thought, maybe it’s because she’ll see a former lover in it. There was much about his rapid success that confused the man. He pressed hard:

– Well, come on.

– Do let me sit here a moment longer (the young woman resisted).

The doctor and his friend went up to surgery and prepared the operation.

The young woman, who was staring at a row of lights downstairs, felt alone after a while, went upstairs and let the men do what they so urgently wanted. When they returned from their activities, the maids were clattering in the hatchway to the dining room. They had put on their bonnets. Evening fell. This could be seen easily through the glass greenhouse windows. Now certainty had been established.

THEY DID NOT COME TO ANY CONCLUSION: A FILM PRODUCER’S MISUNDERSTANDINGS

“Vast amounts of discriminative ability” —Niklas Luhmann

Today we introduce you to a madman who wants to introduce a new type of film to television. He doesn’t want films to have a plot but to describe differences. He’ll explain that to you himself in a moment, said the assistant to the producer. And it was at that moment that Markus M., a commercial artist who had decided to become a film director, walked through the door.

– And what is your film about?

– It’s not about anything, it shows differences, or a difference, so to speak. Cold/warm, bright/dark, velvety soft/rough as concrete, but: light dark-blond/pale brunette, too, it’s got to do with nuances, I tell the hairdresser: just on the edge of dark-blonde, and then I add: light brunette, that’s important.

– But surely you have a storyline, right?

– Nope, don’t need one. Take your fingertip, for example, it’s different from mine.

– And you think that viewers want to see a fingertip? What do you call this new genre of yours?

– We’ve still got to come up with a name!

– I see. And financing? What differences did you have in mind for the beginning?

– That’s something we’d have to think about. You shouldn’t approach filming with any preconceptions.

– What kind of budget were you thinking about?

– Between three and six million dollars.

– Couldn’t you make the project into a low-budget production?

– Then it will cost a hundred and sixty thousand marks.

– And if it’s a real film?

– Then it would be a bit cheaper.

– Interesting. And you can film differences?

– That’s what I said.

– That’s interesting. Commercial?

– You mean commercial differences?

– Can one employ the films commercially?

– As a producer, you should know.

– I do. I’m just asking.

– On a practical level, what does a film producer actually do … ?

– That’s a wide field.

– As opposed to what?

They did not come to any conclusion.

From The Long March of Basic Trust, translated from German by Alexander Booth, to be published by Seagull Books this month.

Alexander Kluge is one of the major German fiction writers of the late twentieth century and an important social critic. As a filmmaker, he is credited with the launch of the New German Cinema movement.

Alexander Booth is a writer and translator. He lives in Berlin.

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)