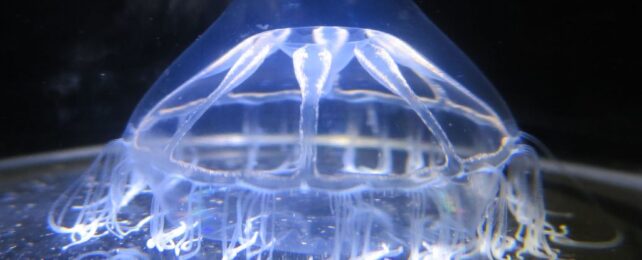

Botrynema brucei ellinorae may look different depending where in the world it lives. (Dhugal Lindsay)

Botrynema brucei ellinorae may look different depending where in the world it lives. (Dhugal Lindsay)

In the cold darkness deep beneath the waves of the Arctic Ocean, a hidden barrier appears to separate the haves from the have-nots.

There, in the midnight zone more than 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) below the surface, the gossamer jellyfish of the subspecies Botrynema brucei ellinorae drifting in the water column have two distinct shapes. Some have hoods topped by a distinctive knob-shaped structure; others are smooth and unknobbed.

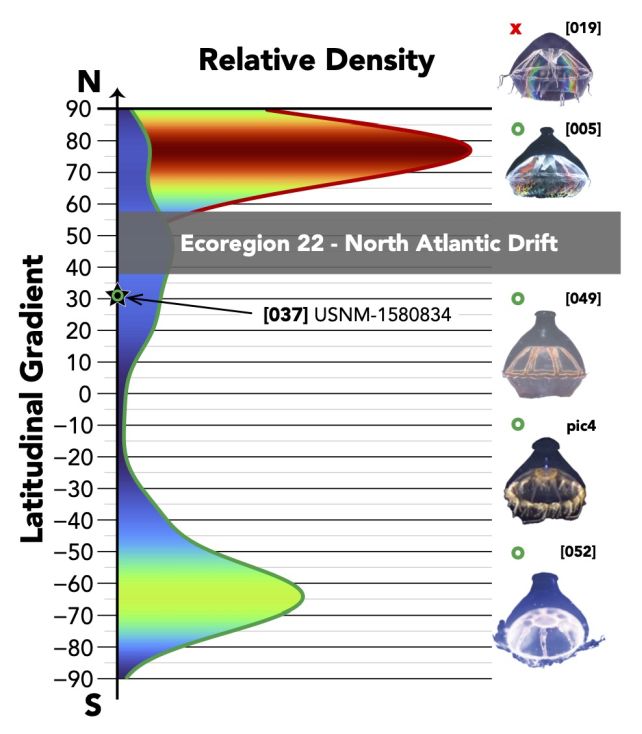

A new survey of the distributions of these two morphotypes has revealed something very strange at a latitude of 47 degrees north.

"Both types occur in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions," explains marine biologist Javier Montenegro of the University of Western Australia, "but specimens without a knob have never been found south of the North Atlantic Drift region, which extends from the Grand Banks off Newfoundland eastwards to north-western Europe."

Related: There's an Invisible Line That Animals Don't Cross. Here's Why.

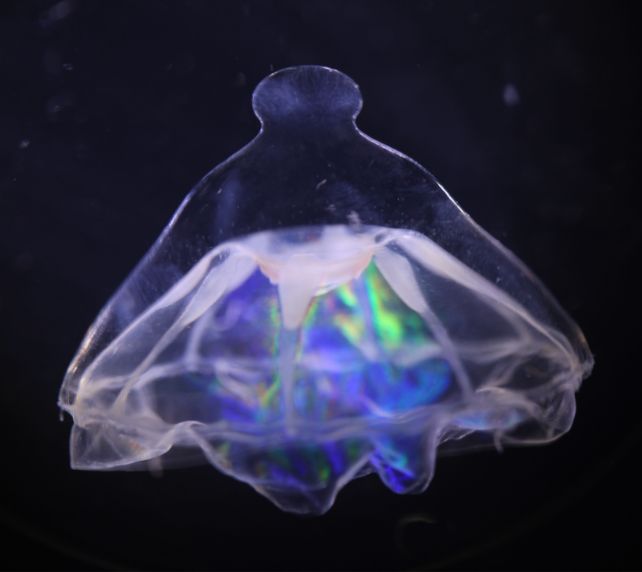

Jellyfish with a knob can be found distributed in deep oceans across the world. (Dhugal Lindsay)

Jellyfish with a knob can be found distributed in deep oceans across the world. (Dhugal Lindsay)At some places in the world, even in the absence of a hard physical barrier, there are lines that separate how animals are distributed. The Wallace Line in the Indonesian archipelago is one; so too are the Lydekker Line and the Weber Line separating the islands of southeast Asia from Australia and Papua New Guinea.

On either side of these lines, the types of animals found in comparable niches are quite distinct. Such lines are known as faunal boundaries, and they can be drawn by environmental differences between two regions, physical barriers that have since disappeared over eons as the world changed, ocean currents, and other factors.

Because they are not clearly demarcated, faunal barriers like this are hard to spot. This difficulty increases exponentially for the deep ocean, a part of the world that is extremely hostile to the human body. Between crushing pressures, freezing temperatures, and the absence of light, the only way we can explore down there is by remote-controlled robots.

Not a single knob-less jellyfish has been found lower than 47 degrees. (Montenegro et al., Deep-Sea Res. I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap., 2025)

Not a single knob-less jellyfish has been found lower than 47 degrees. (Montenegro et al., Deep-Sea Res. I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap., 2025)Montenegro and his colleagues conducted their survey of jellyfish distribution by the collection of specimens, both from research vessels using nets, and remotely-operated underwater vehicles. They also studied historical observations and photographic records.

To their surprise, genetic analysis revealed that the jellyfish with a knob and the jellyfish without a knob belonged to the same genetic lineage. But, while the knobbed jellyfish can be found all over the world, jellyfish without a knob can only be found north of 47 degrees, suggesting a semi-permeable faunal boundary in the North Atlantic Drift region.

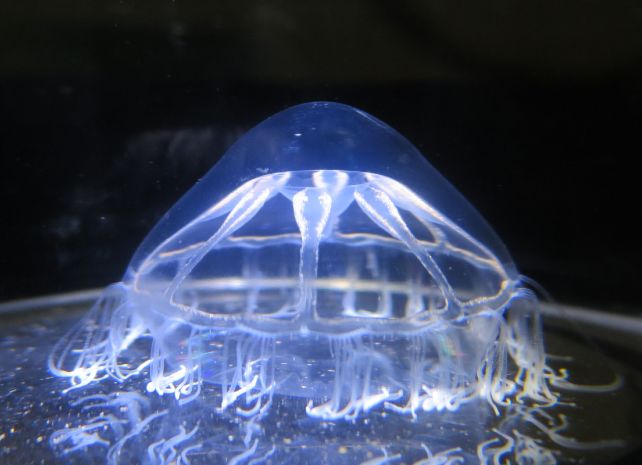

The species mostly lives in deep waters. (Dhugal Lindsay)

The species mostly lives in deep waters. (Dhugal Lindsay)"The differences in shape, despite strong genetic similarities across specimens, above and below 47 degrees north hint at the existence of an unknown deep-sea bio-geographic barrier in the Atlantic Ocean," Montenegro says.

"It could keep specimens without a knob confined to the north while allowing the free transit of specimens with a knob further south, with the knob possibly giving a selective advantage against predators outside the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions."

Northern waters are dominated by knob-less jellyfish. (Dhugal Lindsay)

Northern waters are dominated by knob-less jellyfish. (Dhugal Lindsay)Further research is necessary to determine what creates this invisible barrier keeping the knob-less jellyfish confined to Arctic and sub-Arctic waters, although previous research describes the North Atlantic Drift region as a "transition ecotone with admixture of boreal and subtropical species." This suggests a dividing line between environmental conditions.

The finding underscores just how little we know about the deep ocean, and suggests that other such barriers may be scattered throughout the globe. It also suggests that a comprehensive understanding of the life that teems the ocean yet eludes us.

"The presence of two specimens with distinctive shapes within a single genetic lineage highlights the need to study more about the biodiversity of gelatinous marine animals," Montenegro says.

The research has been published in Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3

English (US)

English (US)