Current medical screening techniques could be failing to catch nearly half of those who experience a heart attack, according to new research, suggesting many of the millions of heart attacks that happen each year could be prevented with improved methods.

In the US, heart attack risk is typically assessed according to a set of criteria such as an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) score, which measures factors linked to the development of cardiovascular disease. Patients are then monitored or treated if their scores exceed a certain threshold.

Researchers from the US and Canada gathered the health records of 465 people 65 years or younger who had been treated for their first heart attack between January 2020 and July 2025 at one of two US medical centers. The data included details such as medical history, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels.

Related: Is Melatonin Bad For Your Heart? An Expert Explains The New Findings.

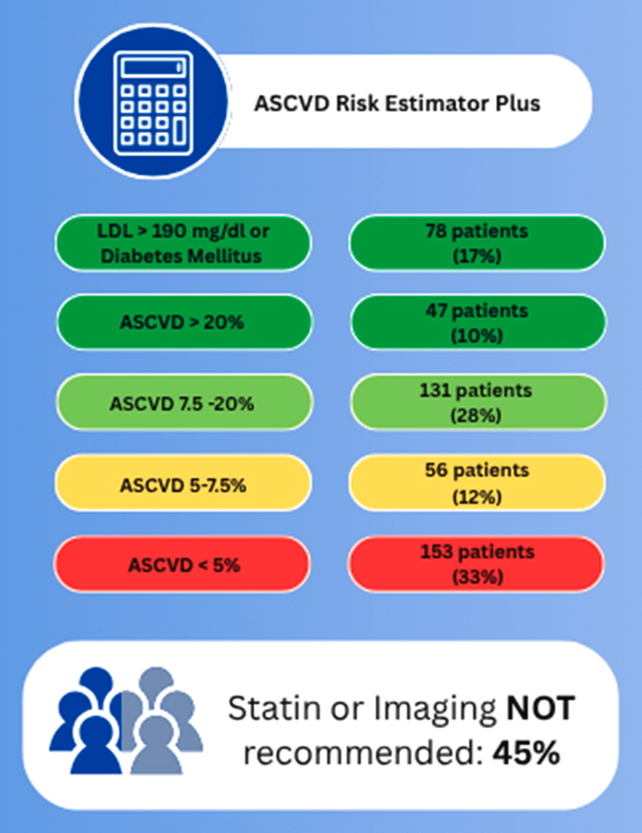

Based on the team's analysis, two days before their heart attack, ASCVD scores would have categorized 45 percent of the patients at low or borderline risk levels. An alternative set of criteria, called a predicting risk of cardiovascular disease events (PREVENT) score, fared even worse: 61 percent of the patients would have been classified as low or borderline risk.

"Our research shows that population-based risk tools often fail to reflect the true risk for many individual patients," says Amir Ahmadi, a cardiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in the US.

"If we had seen these patients just two days before their heart attack, nearly half would not have been recommended for further testing or preventive therapy guided by current risk estimate scores and guidelines."

The ASCVD score could be missing people who will soon experience a heart attack. (Mueller et al., JACC Adv., 2025)

The ASCVD score could be missing people who will soon experience a heart attack. (Mueller et al., JACC Adv., 2025)In the US, the ASCVD score is calculated during annual check-ups for those aged between 40 and 75. It determines the risk of a heart attack or stroke within the next 10 years based on contributing factors such as blood pressure, cholesterol, age, sex, and race.

Those identified as being at intermediate or high risk of a heart attack – high risk being a 20 percent or higher chance of an incident over the next decade – are typically put on preventative measures such as statins.

The researchers suggest that more needs to be done to better assess heart attack risk in groups without any symptoms – people who wouldn't have been flagged by these current tools – perhaps by actually testing for signs of atherosclerosis (the fatty plaques in the arteries that obstruct blood flow).

"When we look at heart attacks and trace them backwards, most heart attacks occur in patients in the low or intermediate risk groups," says Anna Mueller, an internal medicine resident at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

"This study highlights that a lower risk score, along with not having classic heart attack symptoms like chest pain or shortness of breath, which is common, is no guarantee of safety on an individual level."

This research needs to be put in some context: the case histories of only a few hundred people were analyzed retrospectively, and PREVENT scores have shown promise in detecting heart attack risk in large groups of people, for example.

Nevertheless, those scores also seem to miss people who don't present with typical symptoms or risk factors, according to the researchers. If better, more personalized approaches can be found, heart disease can be spotted and prevented earlier.

"This study suggests that the current approach of relying on risk scores and symptoms as primary gatekeepers for prevention is not optimal," says Ahmadi.

The research has been published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Advances.

.jpg) 11 hours ago

3

11 hours ago

3

English (US)

English (US)