Since astronomers discovered the first world outside the solar system in the mid-1990s, these extra-solar planets or "exoplanets" have astounded us with their strange characteristics.

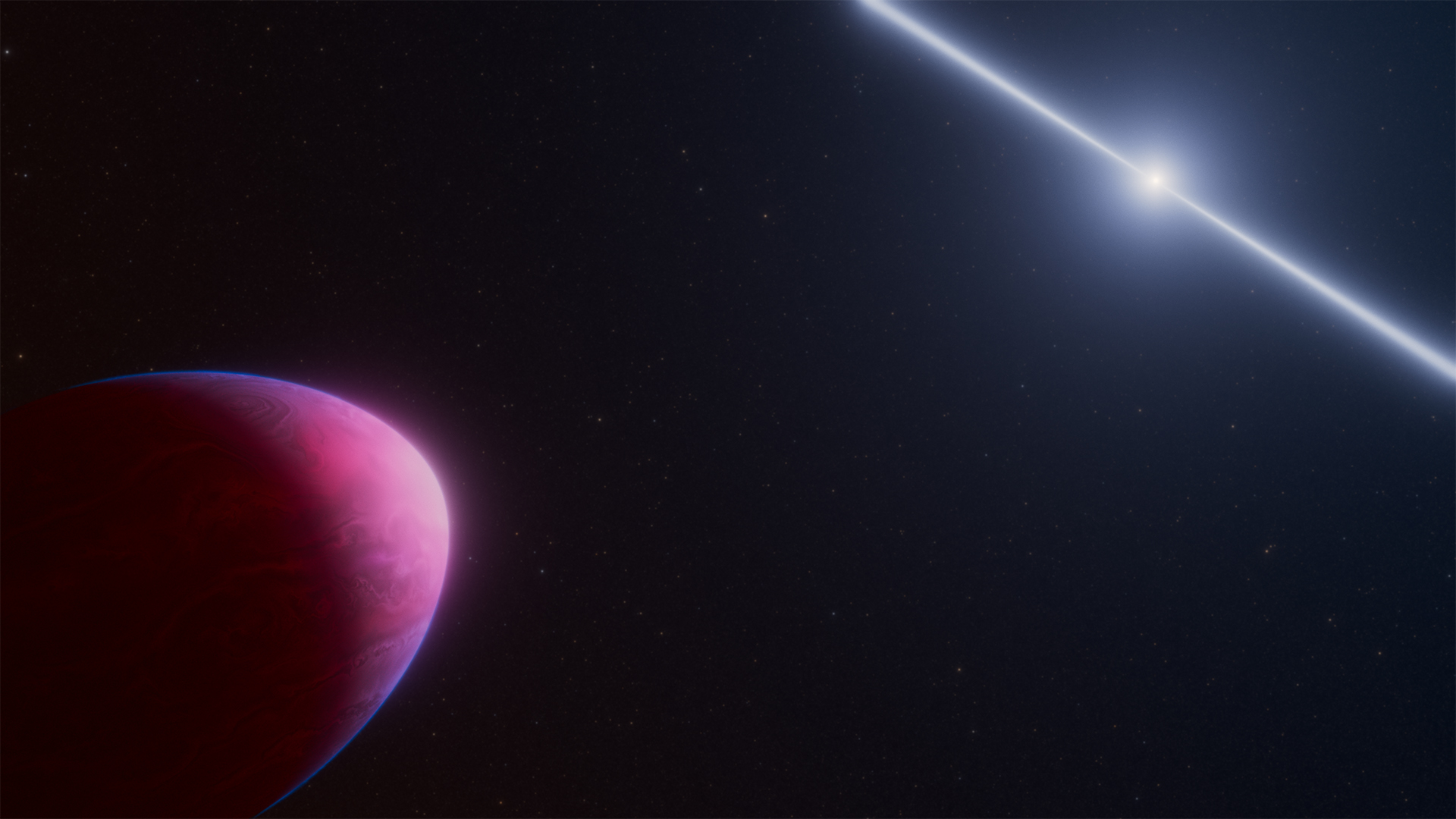

A new discovery, made using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), may just be the weirdest exoplanet yet, possessing an atmosphere unlike any we've ever seen on an exoplanet. Currently, the team behind this discovery can't explain how such a planet came to be.

That isn't in itself so strange. The first planets beyond the solar system ever confirmed, Poltergeist (PSR B1257+12 B) and Phobetor (PSR B1257+12 C), spotted in 1992, also orbit pulsars, a young, rapidly spinning form of neutron star.

However, what sets PSR J2322-2650b apart are the facts that it has an ellipsoid shape, like a planetary lemon or football, and that it has an atmosphere like none scientists have ever seen before.

"This was an absolute surprise," team member Peter Gao of the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory said in a statement. "I remember after we got the data down, our collective reaction was 'What the heck is this?' It's extremely different from what we expected."

The atmosphere of PSR J2322-2650b is dominated by helium and carbon, and likely has clouds of carbon soot that condense to create diamonds that rain down onto the planet.

At just around 1 million miles (1.6 million km) from its pulsar parent star (the Earth is around 100 times as distant from the sun), PSR J2322-2650b completes an orbit once every 8 hours or so. Its lemon-like shape emerges from tidal forces generated within the planet by the powerful gravity of the dead star it clings to.

"A new type of planet atmosphere that nobody has ever seen before"

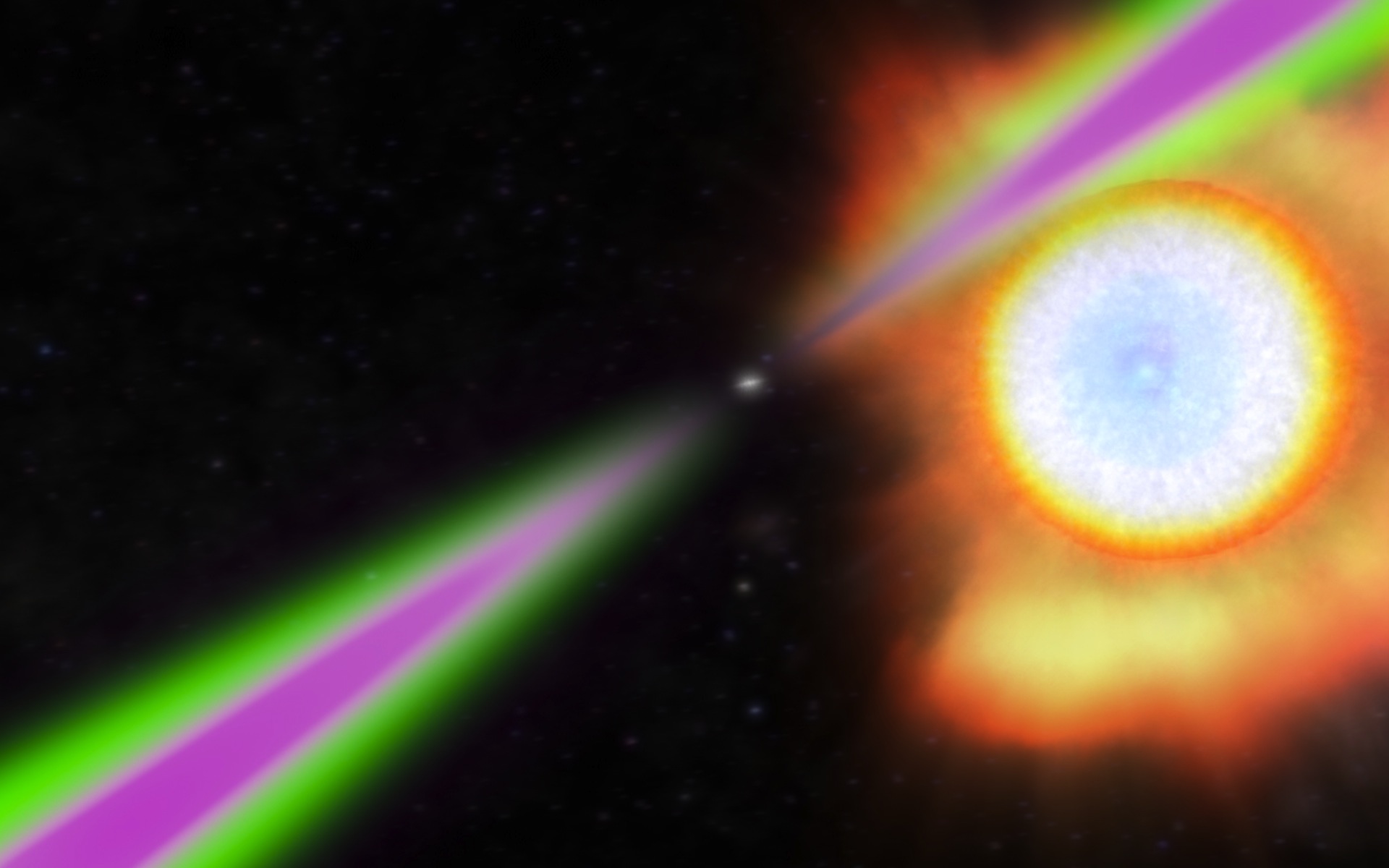

Like all neutron stars, pulsars are born when massive stars at least 10 times the size of the sun exhaust the fuel for nuclear fusion. This results in the star's outer layers, and most of its mass, being blown away in a supernova explosion.

Left behind is a core with between 1 and 2 times the mass of the sun that crushes down to a width of around 12 miles (20 kilometers), and because it retains angular momentum, it can spin as fast as 700 times per second!

The parent star of PSR J2322-2650b is just such a so-called millisecond pulsar, but while it blasts out intense gamma-ray radiation, it doesn't emit very much infrared light. Because the JWST has been designed to see the cosmos in infrared, that means this powerful dead star doesn't block the $10 billion space telescope's view of PSR J2322-2650b.

This allowed the team to investigate the atmosphere of PSR J2322-2650b in detail and uncover its unique composition.

"This is a new type of planet atmosphere that nobody has ever seen before," team leader Michael Zhang of the University of Chicago said. "Instead of finding the normal molecules we expect to see on an exoplanet — like water, methane, and carbon dioxide — we saw molecular carbon, specifically carbon-3 and carbon-2."

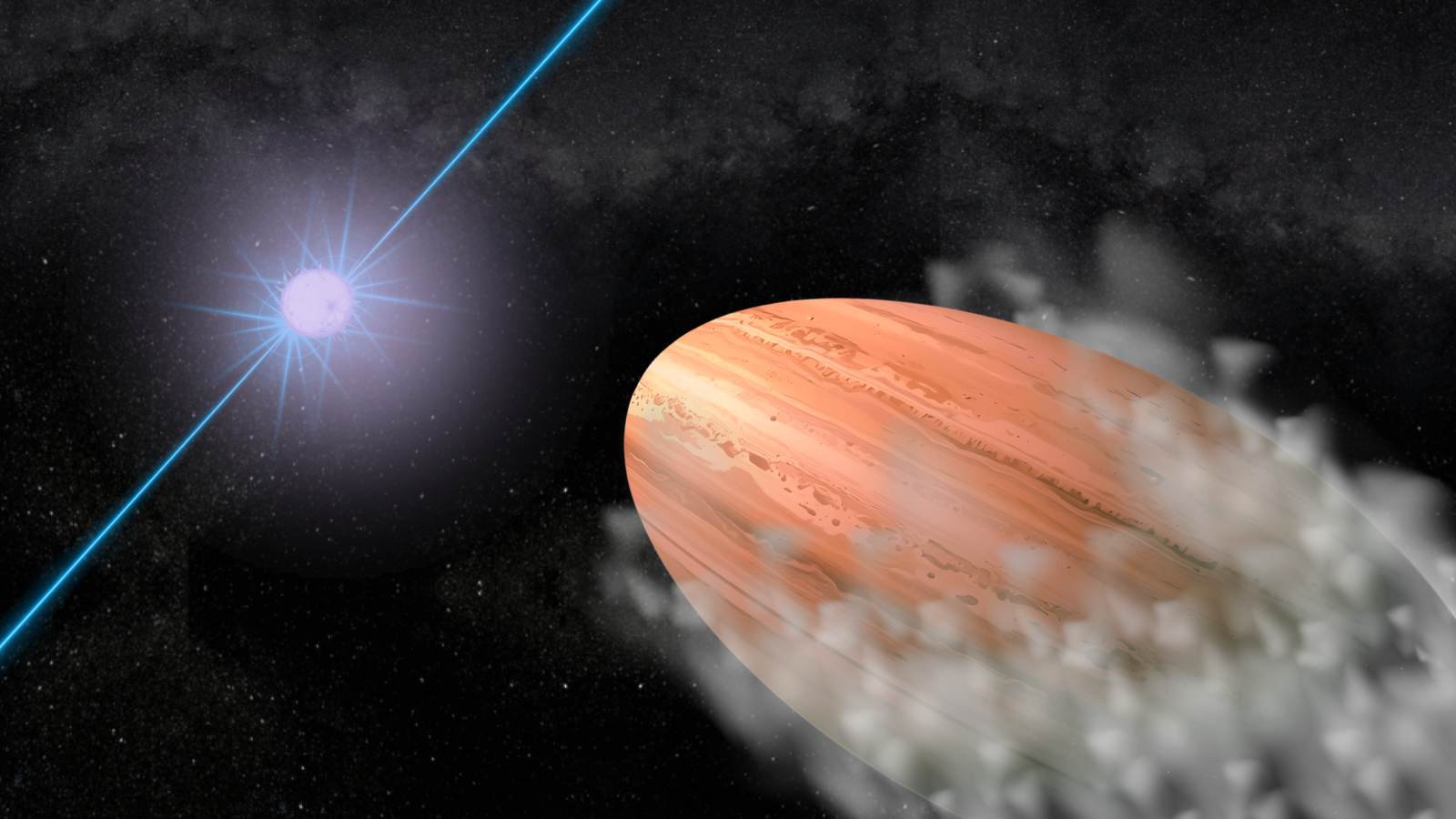

PSR J2322-2650b is tidally locked to its star, which means one side permanently faces the neutron star, the planet's dayside, while the other faces out into space in perpetuity, its nightside.

The dayside of PSR J2322-2650b has a maximum temperature of 3,700 degrees Fahrenheit (2,040 degrees Celsius), while the nightside has a minimum temperature of 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit (650 degrees Celsius).

At these temperatures, molecular carbon should bind with other types of atoms, only becoming dominant if there is almost no oxygen or nitrogen in the planet's atmosphere. Of the 150 or so exoplanet atmospheres studied to date, no others have possessed detectable molecular carbon.

"Did this thing form like a normal planet? No, because the composition is entirely different," Zhang said. "Did it form by stripping the outside of a star, like 'normal' black widow systems are formed?

"Probably not, because nuclear physics does not make pure carbon. It's very hard to imagine how you get this extremely carbon-enriched composition. It seems to rule out every known formation mechanism."

There is one possible route of the creation of this planet, hinging on a unique phenomenon occurring in the bizarre atmosphere of PSR J2322-2650b.

"As the companion cools down, the mixture of carbon and oxygen in the interior starts to crystallize. Pure carbon crystals float to the top and get mixed into the helium, and that's what we see," team member and Stanford University researcher Roger Romani said. "But then something has to happen to keep the oxygen and nitrogen away. And that's where the mystery comes in.

“But it's nice not to know everything. I'm looking forward to learning more about the weirdness of this atmosphere. It's great to have a puzzle to go after."

.jpg) 1 hour ago

2

1 hour ago

2

English (US)

English (US)