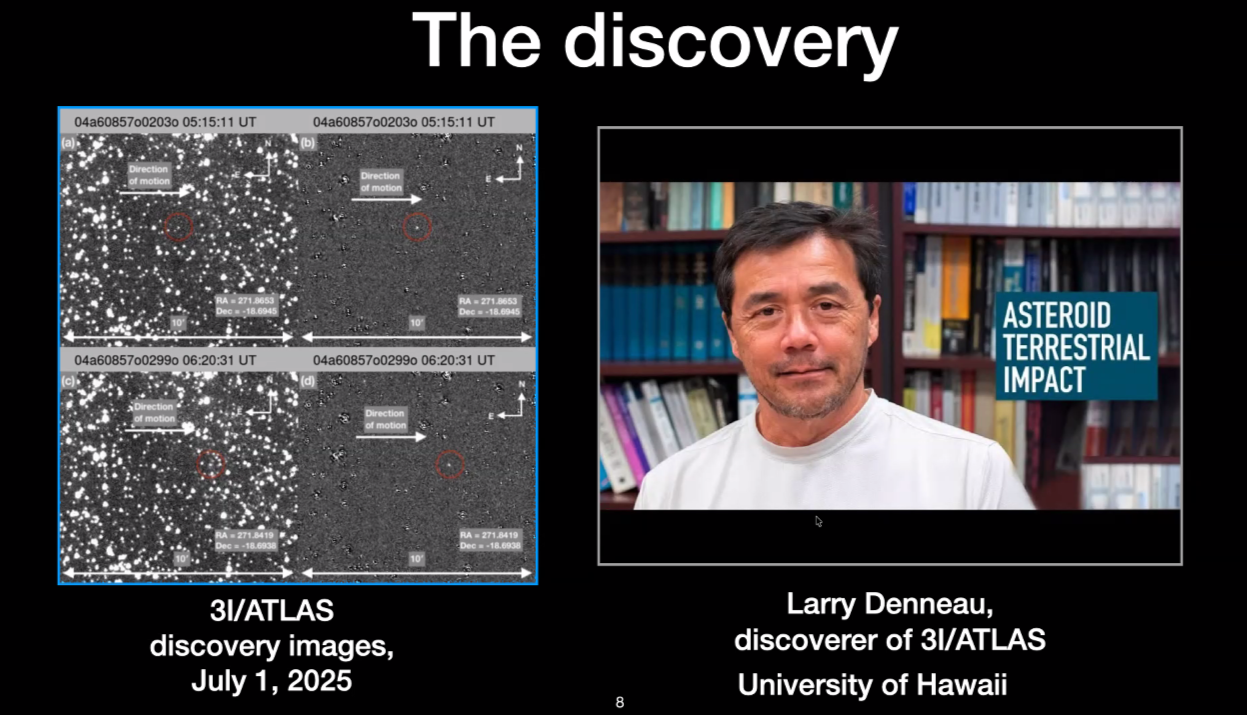

What seemed to be just a normal evening on July 1, 2025 for Larry Denneau, senior software engineer and astronomer at the University of Hawaii's Institute for Astronomy began the same way hundreds of nights before it had: with data quietly rolling in from telescopes scanning the night sky.

Denneau is part of the team behind ATLAS — short for Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System — a network of wide-field telescopes that repeatedly images huge swaths of sky to catch anything that moves, particularly near-Earth asteroids. The system snaps the same patch of sky four times in quick succession to create a short motion path, or "tracklet" that shows possible movement, then uses reference images where the sky is still to subtract out any stars and galaxies, leaving behind moving points that could be asteroids, comets, or something else. Candidates that survive these automated filters are sent to a human reviewer to verify they're real and ready to be catalogued by the Minor Planets Center.

That July evening, one of those survivors landed in front of Denneau. When 3I/ATLAS first showed up in the ATLAS software, it didn’t look special at all. "I was the person reviewing at the time that 3I popped out of the pipeline," Denneau told Space.com "And at the time, it looked like a completely garden variety new Near Earth Object." So Denneau did as the software he designed recommended he do. He clicked "submit."

When the discovery of a new interstellar object lit up astronomers' inboxes around the world, Larry Denneau was nowhere near his email.

He was up in the mountains at Mauna Loa, high on Hawaii's Big Island, servicing a telescope. For an entire day, he was effectively offline, while excitement quietly built around a strange object moving across the solar system.

When he finally got back that night, reality hit all at once.

"I was oblivious to them until we got back that night," he said. "And my inbox was completely exploded with all of this stuff […] At that point, we're thinking about where is it, how fast is it going? Within a day, because this object is so interesting, there are hundreds of observations from different telescopes all confirming the orbit."

The object was classified by the Minor Planets Center as 3I/ATLAS, only the third-known interstellar visitor ever observed passing through our solar system, following 1I/'Oumuamua's discovery in 2017 and 2I/Borisov's in 2019. Unlike typical asteroids or comets, interstellar objects are not gravitationally bound to the sun; they originate around other stars and are briefly visible to us only as they pass through our solar system.

To find these objects, software like the type ATLAS uses looks for any moving objects, just points of light shifting against a background of stars.

"What comes out of our pipeline are really positions," Denneau said. "Things that look like stars that are moving across the background."

At that stage, a human still has to make the call. Someone has to look at the data and decide whether it's real.

"So, yeah," Denneau said, "I'm literally the person who clicked the button and submitted the discovery observations for this object."

Only later did the oddities become clear, especially in the models showing from where 3I/ATLAS might have been moving. As Denneau explained, "Folks with follow-up telescopes go to these places in the sky and they'll see the thing moving in the direction that it’s supposed to be moving. And they'll send in the observations and then Minor Planet Center and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, at the same time, will fit the observations to the orbit and try to compute what the orbit should be."

These follow-up observations and models showed that the object's orbit didn’t behave like anything bound to the sun.

"All of the orbit fits turned out to be really poor," Denneau said. "They didn’t look like the solar system — they had this funny trajectory that said it's going really fast. It's not bound to the sun."

That's when it became obvious: this was something from outside our solar system entirely.

"I was getting asked by JPL, do we have any earlier possible observations that can confirm the trajectory and stuff?" He added. "So we scrambled to try to find some more observations from previous nights."

Where engineer meets astronomer

Denneau doesn't fit the traditional mold of an astronomer. He didn't start his career studying stars or planets — he started with code.

"I'm sort of a non-traditional astronomer," he said. "I started out my career in engineering, mostly computer programming, and so my degree is in EE actually, and not in physics or astronomy." Denneau eventually did receive a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Queen's University Belfast, but continued to use his software skills to shape his career.

After moving to Hawaii and working as the software architect for the asteroid detection pipeline on the Pan-STARRS telescope project, Denneau became deeply involved in building the software systems that modern sky surveys depend on. He eventually joined ATLAS, a NASA-funded project designed to scan the sky every night for near-Earth asteroids. From Denneau's perspective, astronomy depends on a mix of hardware and software.

"We built some telescopes," Denneau said, "but after the telescopes are built, it's really a software project." It would be that software project, one that Denneau helped develop, that would eventually capture images of an interstellar comet.

Each night, ATLAS telescopes take thousands of images of the sky. Because the system uses wide-field lenses, it can cover an area of the sky more than 100 full moons at once. This adds up to an area the size of nearly the entire visible sky every 24 hours, repeatedly revisiting the same regions to look for motion. Those images are automatically transferred, processed, compared and filtered by custom software designed to find anything that moves, especially asteroids close to Earth.

"We have automated software that controls the telescopes, copies the data to Honolulu and then searches these images […] for things that are moving," Denneau explained. That volume is intense as "four or five telescopes combined take a good fraction of a terabyte of data every night," he added. "We're a multi-petabyte project at this point. And so that's the kind of stuff that, as a computer person, keeps me awake, because it’s a lot of data to keep secure and backed up."

That’s why, for Denneau, studying the stars is more of a software project as opposed to a hardware project, as the system has to ingest, clean, subtract, detect, match and archive, all while helping to filter out false positives that could waste other astronomers’ time chasing ghosts.

"We're really sensitive to not wanting to put false things on the confirmation page," Denneau said. "Because other telescopes will spend precious telescope time chasing something that's not real."

ATLAS aims for near-perfect reliability before sending out an alert. "We want to be like 99-point-something-percent reliable on that front," he added.

Detecting other moving objects

Not only was Denneau the person who initially detected 3I/ATLAs using his software, but just months earlier, he'd also been the one on duty for another discovery: near-Earth asteroid YR4.

As with most ATLAS detections, YR4 first appeared as a faint moving point pulled out of the background. Denneau checked the detections and confirmed that they were real before sending the data to the Minor Planets Center. The building-sized YR4 was initially thought to only have slim chances of hitting Earth on Dec. 22, 2032. However, with more study from astronomers, NASA concluded that YR4 actually poses no significant impact threat at all.

Why 3I/ATLAS was hard to detect

Unlike YR4, finding earlier observations of 3I/ATLAS to model where it might have come from was easier said than done. During its July 1, 2025 detection, the interstellar object happened to be moving through a particularly crowded part of the sky, packed with stars from the Milky Way. That made detection much harder.

ATLAS requires four clean detections to officially flag a new object. Until 3I/ATLAS moved into a less cluttered region of the sky, it stayed hidden in the noise, which is most likely why it wasn't detected sooner.

"When there's so many stars in the background, sometimes an asteroid goes right on top of a star," Denneau explained. "And so you only get three out. Because it was in the Milky Way, we had to kind of wait for it to get to a less dense part of the sky, for our pipeline to automatically admit it. And so we got it a week later than we actually first thought." Once 3I/ATLAS did move to a less dense area, the software worked exactly as designed, and even dug up earlier, "precovery" observations that helped confirm its unusual orbit.

Since its initial classification, 3I/ATLAS's popularity has spilled from the astronomy community into headlines and social media feeds. Interstellar visitors are still so rare that each one captures the public imagination and 3I/ATLAS is no exception. Each of these objects offers a fleeting, invaluable glimpse of material formed around another star.

And in this case, that glimpse began not with a dramatic telescope view, but with software, data, and one person clicking a button at exactly the right time.

"Every day I still love coming to work and working on astronomy," Denneau said. "It's just super fun."

.jpg) 1 hour ago

3

1 hour ago

3

English (US)

English (US)