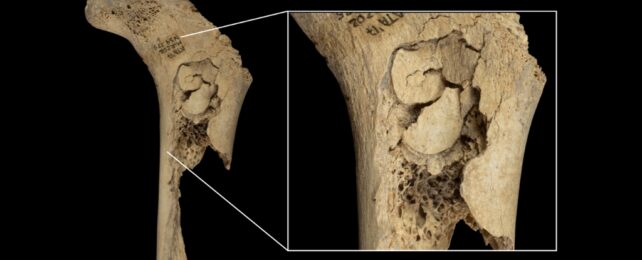

The femur of an infant with crush marks consistent with bone marrow extraction. (IPHES-CERCA)

The femur of an infant with crush marks consistent with bone marrow extraction. (IPHES-CERCA)

Humans living on the Iberian Peninsula during the late Neolithic period may have eaten their neighbors in one grim and grisly act of social violence, new evidence reveals.

At least 11 individuals – including children and adolescents – appear to have been skinned, defleshed, disarticulated, fractured, cooked, and eaten by other people, according to the marks on bones dating back to 5,709–5,573 years ago, found in El Mirador cave in Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain.

Even more intriguingly, the evidence suggests that all of this cannibalism occurred at around the same time, in a single, possibly isolated incident. This suggests that the people living there at the time were not habitual cannibals, but may have engaged in the practice for extenuating reasons, such as local inter-clan conflict.

Related: Cannibalism in Europe's Past Was More Common Than You May Realize

"In this study we are dealing with a new case of cannibalism at the Atapuerca sites," says paleoecologist Palmira Saladié of the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES) in Spain.

"Cannibalism is one of the most complex behaviors to interpret, due to the inherent difficulty of understanding the act of humans consuming other humans. Moreover, in many cases we lack all the necessary evidence to associate it with a specific behavioral context. Finally, societal biases tend to interpret it invariably as an act of barbarism."

A large number of bones showed signs of being butchered and the flesh eaten. (IPHES-CERCA)

A large number of bones showed signs of being butchered and the flesh eaten. (IPHES-CERCA)Humanity's ancient history appears to be riddled with smatterings of cannibalism throughout the millennia, with the practice appearing in multiple instances in the Iberian Peninsula alone.

There are many reasons why our ancestors may have practiced cannibalism, ranging from sustenance to the funerary rite of transumption – incorporating the deceased into the bodies of the living to symbolically keep them alive.

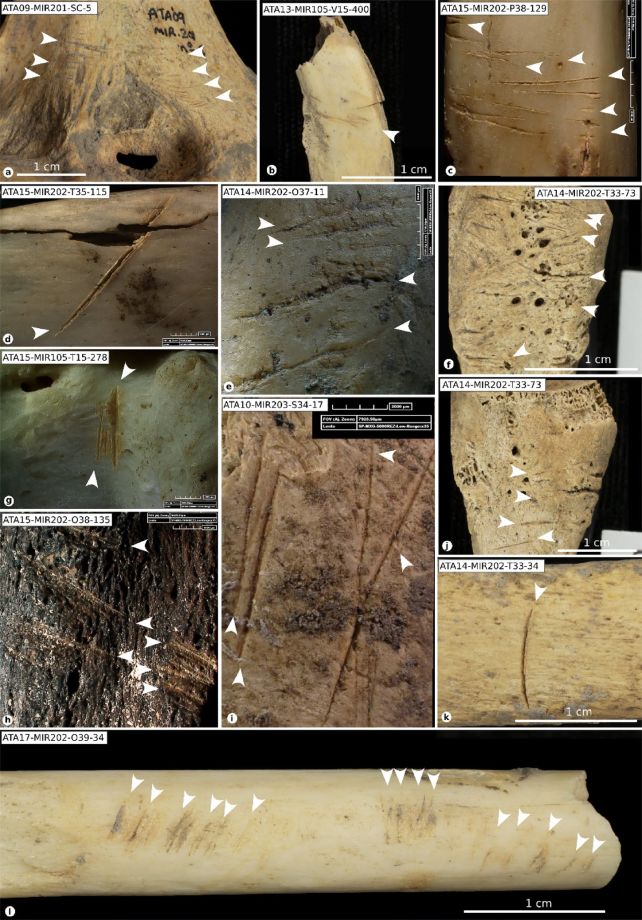

Some of the cut marks cataloged by the researchers. (Saladié et al., Sci. Rep., 2025)

Some of the cut marks cataloged by the researchers. (Saladié et al., Sci. Rep., 2025)Saladié and her colleagues found their strange cannibalism incident documenting 650 individual fragments of human bones from El Mirador cave that showed signs of what is called processing after death – deliberate alteration.

These signs include 'pot-polishing', the smoothing of the ends of the bones associated with being tossed in a cooking pot; discoloration associated with cremation; and cut marks on 132 of the bones, consistent with "defleshing, skinning, disarticulation, dismembering, and evisceration," the researchers write.

Some bones also showed a type of alteration known as peeling. How peeling occurs is debated among scientists, but one possible mechanism is from being bitten – tooth marks. Some of the remains in their assemblage, the researchers say, show pretty clear signs of having been gnawed by human teeth.

These bones show damage that may be the result of being chewed. (Saladié et al., Sci. Rep., 2025)

These bones show damage that may be the result of being chewed. (Saladié et al., Sci. Rep., 2025)It gets even more intriguing. Radiocarbon dating suggested that all the devoured humans died at around the same time and were butchered and eaten in one event, perhaps spanning several days. An analysis of the strontium isotope ratios in the bones showed that all the consumed people were local.

"This was neither a funerary tradition nor a response to extreme famine," says IPHES evolutionary anthropologist and quaternary archaeologist Francesc Marginedas. "The evidence points to a violent episode, given how quickly it all took place – possibly the result of conflict between neighboring farming communities."

We'll never know for certain what led to the horrifying feast of human flesh in El Mirador some 5,700 years ago, but the evidence points to an extreme demonstration for the purposes of social control, the researchers say.

"Conflict and the development of strategies to manage and prevent it are part of human nature," says archaeozoologist Antonio Rodríguez-Hidalgo of IPHES. "Ethnographic and archaeological records show that even in the less stratified and small-scale societies, violent episodes can occur in which the enemies could be consumed as a form of ultimate elimination."

A growing body of evidence increasingly indicates widespread, inter-group violence on the Iberian Peninsula during the Neolithic – probably due to territorial disputes, competition over resources, and population pressure as more and more people migrated into the region.

The butchered bones suggest that cannibalism was part of this landscape of violence, an extreme tool in a larger kit used to completely subdue one's foes.

It also contributes some nuance to our understanding of cannibalism throughout human history.

"The recurrence of these practices at different moments in recent prehistory makes El Mirador a key site for understanding prehistoric human cannibalism and its relationship to death, as well as possible ritual or cultural interpretations of the human body within the worldview of those communities," Saladié says.

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.

.jpg) 3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3

English (US)

English (US)