Thousands of years ago, people on what is now the Danish island of Bornholm threw hundreds of mysteriously carved stones into a ditch before burying them.

The purpose of these so-called 'sun stones', and the reasons for throwing them into ditches en masse, have been something of a mystery – but ancient ice excavated from Greenland may have the answer.

Some 4,900 years ago, a volcano erupted so massively that it would have blotted out the Sun – prompting the ritual sacrifice of sun stones in a bid to restore it.

"We have known for a long time that the Sun was the focal point for the early agricultural cultures we know of in Northern Europe," says archaeologist Rune Iversen from the University of Copenhagen.

"They farmed the land and depended on the Sun to bring home the harvest. If the Sun almost disappeared due to mist in the stratosphere for longer periods of time, it would have been extremely frightening for them."

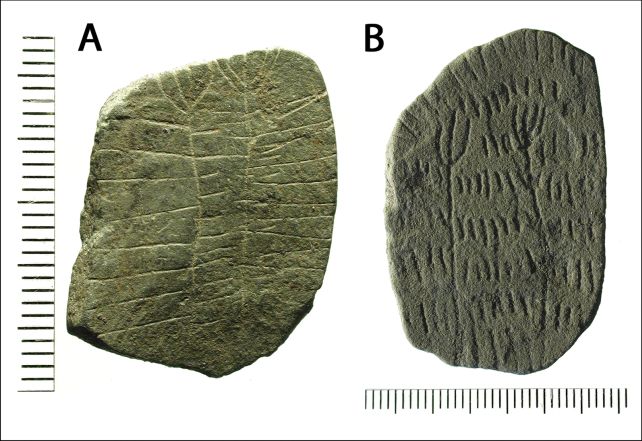

Two of the Vasagård stones, carved with field and plant motifs. (René Laursen, Bornholms Museum/Iversen et al., Antiquity, 2025)

Two of the Vasagård stones, carved with field and plant motifs. (René Laursen, Bornholms Museum/Iversen et al., Antiquity, 2025)Sun stones – or "solsten" in Danish – have been found in great numbers at an archaeological site on Bornholm called Vasagård. The site, in use between around 3500 BCE and 2700 BCE, is thought to have been a religious complex; more specifically a place of Sun worship, as the entrances to the complex line up with the Sun at the time of the solstices.

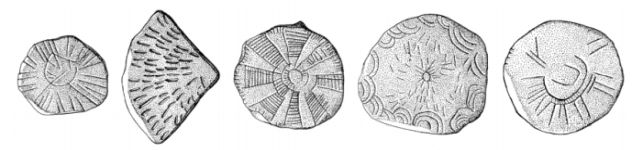

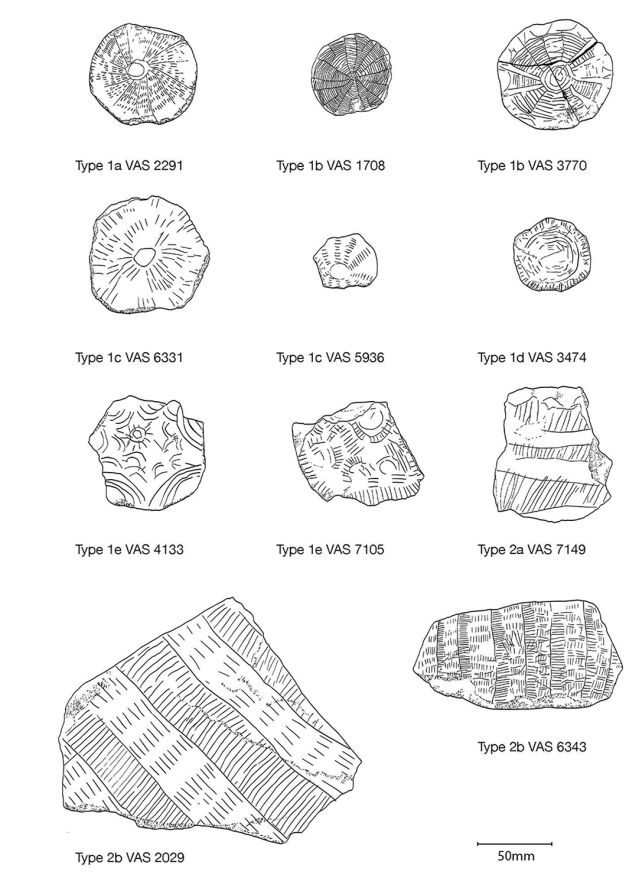

Buried in ditches next to a causeway that runs through the site, archaeologists have excavated more than 600 whole or fragmented sun stones. These are mostly palm-sized, usually flat, rounded stones that are engraved with lines that radiate out from center, like the rays of the Sun, although there is some variation in the shape of the stone and the patterns engraved upon them.

Taken together, they represent hours upon hours of painstaking carving. Such deliberate work must have had a purpose, and archaeologists believe that this purpose was spiritual, concerning the Sun, fertility, and growth.

Some of the patterns engraved on the stones. (Bjørn Skaarup, the National Museum of Denmark)

Some of the patterns engraved on the stones. (Bjørn Skaarup, the National Museum of Denmark)"Sun stones were found in large quantities at the Vasagård West site," Iversen says, "where residents deposited them in ditches forming part of a causewayed enclosure together with the remains of ritual feasts in the form of animal bones, broken clay vessels, and flint objects around 2900 BCE. The ditches were subsequently closed."

The clustering of these stones in time and space suggests a specific purpose or event. Iversen and his colleagues believe that they have identified what that event might be in an ice core extracted from the Greenland ice sheet, annual sediment layers from ancient lakebeds, and tree rings that formed around the same time.

In the ice core, in a layer deposited around 2900 BCE, a significant amount of sulfate can be seen, a signature that is seen when a volcano massively erupts, and its ejecta settles onto an ice sheet and is buried by subsequent ice layers.

Some of the different patterns seen on the stones. (Bente Stensen Christensen/Iversen et al., Antiquity, 2025)

Some of the different patterns seen on the stones. (Bente Stensen Christensen/Iversen et al., Antiquity, 2025)Annual sediment layers from Germany, known as varves, indicate two periods of low sunlight, with one significantly occurring around 2900 BCE. And tree ring data from bristlecone pines in the western US show very thin rings around the same time period – associated with very cold, dry conditions.

We know that large enough volcanic eruptions can cause widespread problems for several years, such as a period of cooling, low sunlight, crop failure, and subsequent famine. All these lines of evidence, Iversen and his team believe, point to a connection between a volcanic event and the sun stones at Vasagård.

"It is reasonable to believe that the Neolithic people on Bornholm wanted to protect themselves from further deterioration of the climate by sacrificing sun stones – or perhaps they wanted to show their gratitude that the Sun had returned again," he says.

There's one more significant clue. In the years following the deposition of the stones, the design of the site changed significantly. At the same time, plague ravaged the region, and the culture was undergoing a major shift as mass migration took place across Europe.

The location of Vasagård on the island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea. (University of Copenhagen)

The location of Vasagård on the island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea. (University of Copenhagen)If the devastation wrought by a volcanic eruption had come and gone, and with other large changes happening, it's not a large leap to infer that the changing needs of the locals led to the rejigging of their gathering space.

"After the sacrifice of the sun stones, the residents changed the structure of the site so that instead of sacrificial ditches it was provided with extensive rows of palisades and circular cult houses," Iversen says.

"We do not know why, but it is reasonable to believe that the dramatic climatic changes they had been exposed to would have played a role in some way."

The research has been published in Antiquity.

.jpg) 3 hours ago

1

3 hours ago

1

English (US)

English (US)