Modern mammals have unique hearing abilities, able to sense a broad range of volumes and frequencies using middle-ear features, including our eardrums and a few small bones.

A new study from paleontologists at the University of Chicago in the US has revealed these physical features began to emerge nearly 50 million years earlier than we thought.

They found their evidence within a 250-million-year-old fossil of the mammal ancestor, Thrinaxodon liorhinus. Using computed tomography scans of the animal's skull and jaw, they created 3D models that allowed them to simulate how Thrinaxodon's anatomy might have reacted to the different sound pressures and frequencies, using engineering software to see how its bones 'wiggled' in response.

Related: Our Ears Still Try to Swivel Around to Hear Better, Study Discovers

Fossil specimen of the Thrinaxodon skull and jaw used for the study. (Matt Wood/University of Chicago)

Fossil specimen of the Thrinaxodon skull and jaw used for the study. (Matt Wood/University of Chicago)Thrinaxodon lived during the Early Triassic, before the first dinosaurs. It was a cynodont – a close relative of early mammals – with a body that looks somewhere in between a lizard and a fox.

Some of its genes follow the same blueprint modern mammals carry today, and this new study suggests the architecture of its hearing is also something we share.

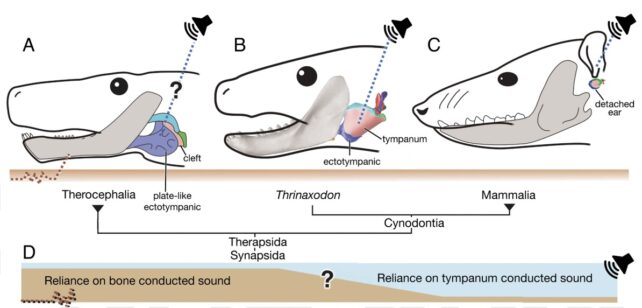

Early cynodonts had ear bones – the malleus, incus, and stapes – that were attached to their jaw. In later species, these tiny fragments eventually became detached from the jaw to form the distinctly mammalian middle ear.

Before the middle ear and its associated 'tympanic' hearing abilities, animals relied on bone-conducted sound, where nerves carry signals from vibrations in the jawbone to the brain.

Paleontologists have speculated for decades that Thrinaxodon may be a 'missing link' in the evolution of mammalian hearing. In 1975, University of Wisconsin anatomist Edgar Allin proposed that Thrinaxodon might have had an early form of an eardrum stretched across the still-attached, hooked bone structure protruding from its jaw.

Evolution of the mandibular middle ear and auditory function through the mammalian evolutionary lineage: a) therapsid, b) Thrinaxodon, c) opossum. (Wilken et al., PNAS, 2026)

Evolution of the mandibular middle ear and auditory function through the mammalian evolutionary lineage: a) therapsid, b) Thrinaxodon, c) opossum. (Wilken et al., PNAS, 2026)But at the time, Allin didn't have the technology to prove his suspicion, which is why the researchers on the new study have now revisited the question with engineering software.

"For almost a century, scientists have been trying to figure out how these animals could hear. These ideas have captivated the imagination of paleontologists who work in mammal evolution, but until now we haven't had very strong biomechanical tests," says Alec Wilken, evolutionary scientist at the University of Chicago.

"We took a high-concept problem – that is, 'how do ear bones wiggle in a 250-million-year-old fossil?' – and tested a simple hypothesis using these sophisticated tools."

The 3D model allowed the team to examine the animal's skull and jawbone in unprecedented detail, including the crook in its jawbone across which an early eardrum might have stretched.

Then, using a tool better known to engineers for testing vibrational stress on infrastructure like planes and bridges, they simulated how Thrinaxodon's skull and jaw would be affected by a range of sounds.

Of course, there's a lot more to a living head than just bone, so the scientists also filled in the gaps using known parameters from living animals about the kinds of soft tissue that might have also been at play.

"Once we have the CT model from the fossil, we can take material properties from extant animals and make it as if our Thrinaxodon came alive," says Zhe-Xi Luo, Wilken's advisor. "That hasn't been possible before, and this software simulation showed us that vibration through sound is essentially the way this animal could hear."

All together, the results suggest Thrinaxodon's eardrum would have worked quite well even without the detached middle-ear bones. And it would have been quite an upgrade on bone conduction, potentially marking a transition point for mammals towards reliance on tympanic hearing.

Wilken and team make a conservative estimate that with this built-in equipment, Thrinaxodon could have achieved a hearing range from 38 to 1,243 hertz (for reference, a healthy young person can hear around 20 to 20,000 hertz), and was most sensitive to sounds at 1,000 hertz when the sound pressure was 28 decibels (a sound level somewhere between a whisper and a normal conversation).

This would have helped Thrinaxodon locate prey, avoid predators, and may have even played a role in reproduction.

The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

.jpg) 2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)